An Over 500 Year Old Samurai Ninjutsu Battle-Sword Katana. Fitted in Total Black For Camouflaged Combat. It’s Simplicity is In Fact Most Elegant. The Black on Black Livery is The Apex of Sophistication As Much For Works Art as For Personal Attire.

A super samurai or even ninjutsu sword, all original Edo fittings, excellent highly distinctive original Edo period full black décor, the hallmark of the traditional Samurai or a ninjutsu combat sword, worn with the intention of displaying no decorative plumage, this sword was for a serious no nonsense samurai or ninja who had no need for displays of status that more embellished swords would have, and would be in fact a great disadvantage. It is why the infamous exponent of the martial art of ninjutsu, the ninja, were often traditionally adorned in all black, armed with an all black mounted sword, in order to remain entirely as unseen and unnoticed as possible, hence their mythical ability to become invisible, not the fantasy of actual invisibility, but the reality of being so unnoticeable and near impossible to see at dusk or at night, they were ‘effectively’ invisible.

Black leather binding over fine dragon and ken shakudo menuki, in turn on fine black giant ray skin. Hilt and saya in dark patinated suite of handachi mounts, and the lacquer in an ishime stone ground finish. The sword bears a powerful blade, in beautiful polish showing a most extravagent hamon and hada.

The swordsmith has signed the tang, Ni Jyu Hachi, that are three nen kanji on the bottom of the nakago, this is very unusual indeed.

The origin of the so-called ninjutsu;

Spying in Japan dates as far back as Prince Shotoku (572–622). According to Shoninki, the first open usage of ninjutsu during a military campaign was in the Genpei War, when Minamoto no Kuro Yoshitsune chose warriors to serve as shinobi during a battle. This manuscript goes on to say that during the Kenmu era, Kusunoki Masashige frequently used ninjutsu. According to footnotes in this manuscript, the Genpei War lasted from 1180 to 1185, and the Kenmu Restoration occurred between 1333 and 1336. Ninjutsu was developed by the samurai of the Nanboku-cho period, and further refined by groups of samurai mainly from Koka and the Iga Province of Japan in later periods.

Throughout history, the shinobi were assassins, scouts, and spies who were hired mostly by territorial lords known as daimyo. Despite being able to assassinate in stealth, the primary role was as spies and scouts. Shinobi are mainly noted for their use of stealth and deception. They would use this to avoid direct confrontation if possible, which enabled them to escape large groups of opposition.

Many different schools (ryū) have taught their unique versions of ninjutsu. An example of these is the Togakure-ryū, which claims to have been developed after a defeated samurai warrior called Daisuke Togakure escaped to the region of Iga. He later came in contact with the warrior-monk Kain Doshi, who taught him a new way of viewing life and the means of survival (ninjutsu).

Ninjutsu was developed as a collection of fundamental survivalist techniques in the warring state of feudal Japan. The ninja used their art to ensure their survival in a time of violent political turmoil. Ninjutsu included methods of gathering information and techniques of non-detection, avoidance, and misdirection. Ninjutsu involved training in what is called freerunning today, disguise, escape, concealment, archery, and medicine. Skills relating to espionage and assassination were highly useful to warring factions in feudal Japan. At some point, the skills of espionage became known collectively as ninjutsu, and the people who specialized in these tasks were called shinobi no mono.

There were no female ninja, however, the late 17th century the ninja handbook Bansenshukai describes a technique called kunoichi-no-jutsu (くノ一の術, "the ninjutsu of a woman") in which a woman is used for infiltration and information gathering, which Seiko Fujita considers evidence of female ninja activity.

.

Han-dachi originally appeared during the Muromachi period when there was a transition taking place from Tachi to katana. The sword was being worn more and more edge up when on foot, but edge down on horseback as it had always been.

A samurai was recognised by his carrying the feared daisho, the big sword daito, little sword shoto of the samurai warrior. These were the battle katana, the big sword, and the wakizashi, the little sword. The name katana derives from two old Japanese written characters or symbols: kata, meaning side, and na, or edge. Thus a katana is a single-edged sword that has had few rivals in the annals of war, either in the East or the West. Because the sword was the main battle weapon of Japan's knightly man-at-arms (although spears and bows were also carried), an entire martial art grew up around learning how to use it. This was kenjutsu, the art of sword fighting, or kendo in its modern, non-warlike incarnation. The importance of studying kenjutsu and the other martial arts such as kyujutsu, the art of the bow, was so critical to the samurai, a very real matter of life or death, that Miyamoto Musashi, most renowned of all swordsmen, warned in his classic The Book of Five Rings: The science of martial arts for warriors requires construction of various weapons and understanding the properties of the weapons. A member of a warrior family who does not learn to use weapons and understand the specific advantages of each weapon would seem to be somewhat uncultivated.

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading

Cutting edge 27 inches long, overall in saya read more

5950.00 GBP

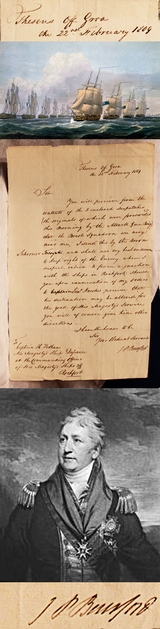

A Despatch From Commodore James Poo Beresford HMS Theseus 2 Feb 1809

Shortly before the Battle of the Basque Roads. Written and signed by Commodore [Later Admiral] Beresford aboard and in command of HMS Theseus. Some few years earlier Theseus was the flagship of Rear Admiral Horatio Nelson's fleet for the 1797 Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Day to day command at that time was vested in her flag captain Ralph Willett Miller. Unfortunately on this occasion the navy was defeated and Nelson was wounded by a musket ball while aboard the Theseus, precipitating the amputation of his right arm. In 1798, Theseus took part in the decisive and hugely successful Battle of the Nile, under the command of Captain Ralph Willett Miller. The Royal Navy fleet was outnumbered, at least in firepower, by the French fleet, which boasted the 118-gun ship-of-the-line L'Orient, three 80-gun warships and nine of the popular 74-gun ships. The Royal Navy fleet in comparison had just thirteen 74-gun ships and one 50-gun fourth-rate.

During the battle Theseus, along with Goliath, assisted Alexander and Majestic, who were being attacked by a number of French warships. The French frigate Artemise surrendered to the British, with the crew setting fire to their ship to prevent it falling into the hands of the British. Two other French ships Heureux and Mercure ran aground and soon surrendered after a brief encounter with three British warships, one of which was Theseus. L'Orient was destroyed in the battle by what was said to be the greatest man made explosion ever to have been witnessed. It was heard and felt over 15 miles distant.

The battle was a success for the Royal Navy, as well as for the career of Admiral Nelson. It cut supply lines to the French army in Egypt, whose wider objective was to threaten British India. The casualties were heavy; the French suffered over 1,700 killed, over 600 wounded and 3,000 captured. The British suffered 218 dead and 677 wounded. Nine French warships were captured and two destroyed. Two other French warships managed to escape. Theseus had five sailors killed and thirty wounded, included one officer and five Royal Marines. A painting in the gallery of Commodore Beresford leading his squadron of ships from 'The Naval Chronology of Great Britain', by J. Ralfe, leading a British squadron of 4 sail of the line near the Isle of Grouais in the face of the French Brest fleet of 8 of the line obliging the French to haul their wind and preventing them from joining the L'Orient squadron. The three ships alongside Beresford were HMS Revenge, Valiant and Triumph, and the Triumph was commanded by none other than Capt. Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy. Beresford was a natural son of Lord de la Poer the Marquess of Waterford. He joined the Royal Navy and he served in HMS Alexander in 1782. He was appointed as a Lieutenant RN serving on H.M.S. Lapwing 1790. He served in H.M.S. Resolution 1794. He served in H.M.S. Lynx (In command) in 1794. He was appointed as Acting Captain RN in 1794 serving in H.M.S. Hussar (In command). He was appointed as a Captain RN (With seniority dated 25/06/1795). He served in H.M.S. Raison (In command) 1795. He served in H.M.S. Unite (In command) 1798. He served in H.M.S. Diana (In command). He served in H.M.S. Virginie (In command) 1803. He served in H.M.S. Cambrian (In command) 1803. He was appointed as a Commodore RN 1806. He was appointed as the Commander-in-Chief in the River St. Lawrence, along the Coast of Nova Scotia, the islands of St. John and Cape Breton and in the Bay of Fundy and the Islands of Bermuda. He served in H.M.S. Theseus (In command) 1808. He served in H.M.S. Poitiers (In command) 1810. He served on to the staff of Lord Wellington at Lisbon Portugal 1810. During the War of 1812, he served as captain of HMS Poictiers, during which time he ineffectually bombarded the town of Lewes in Delaware. More importantly, Poictiers participated in an action where, four hours after USS Wasp, commanded by Jacob Jones, captured HMS Frolic, Capt Beresford captured Wasp and recaptured Frolic, and brought both to Bermuda. He was appointed as a Commodore RN in 1813. He served in HMS Royal Sovereign (In command) 1814. He was appointed as a Rear Admiral of the Blue (With seniority dated 04/06/1814). He was appointed as Commander-in-Chief at Leith 1820-23. He was appointed as the Commander-in-Chief at The Nore 1830-33. He was appointed as a Vice Admiral RN (With seniority dated 27/05/1825). He was appointed as a Junior Lord of the Admiralty in 1835. He was finally appointed as a Admiral RN (With seniority dated 28/06/1838). The typed transcript shown in the gallery states 'mediant servant' of course it should be 'obedient servant' read more

1975.00 GBP

Another Fabulous Selection To Arrive Here Next Week, Soon to Be Added On To The Lanes Armoury Website, Due In From Our Conservation Workshop

A wonderful selection of Napoleonic, French, British and Russian Swords, Antique Japanese Samurai Katanas, and WW2 Japanese Shin Gunto officer's swords, a stunning French Dragoon Helmet, several 1st Editions of P.G.Wodehouse's, Bertie Wooster, plus, lots more as usual

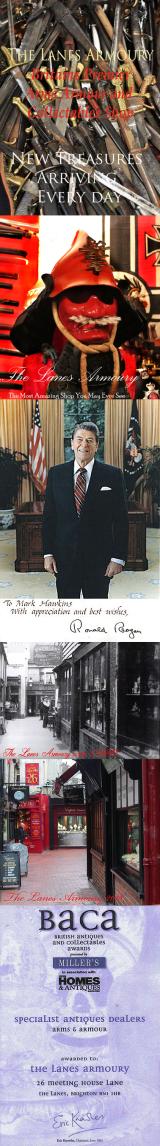

The Lanes Armoury is many things, including, but not exclusively, Europe’s Leading Original Samurai Sword & Armoury Antiques Gallery.

After over 50 years personal experience as a partner and director by Mark, since 1971, and over 40 years by David, we are Europe’s leading original samurai sword gallery, with hundreds of swords to view and buy online 24/7, or in our gallery in Brighton on a personal visit, 6 days a week.

It has been said that the Hawkins family have, in their sword dealing history, handled, bought and sold more original Japanese swords than any other sword dealers outside of Japan since World War I, numbering well into the tens of thousands of samurai weapons. In fact we still know of no better and varied original samurai sword selection, for sale under one roof, anywhere in the world today outside of Japan, or possibly, even within it. Hundreds of antique pieces for sale to choose from, and some up to 800 years old. We have had personal dealings {both buying and selling} with curators, experts and collectors from numerous leading museums around the world, {including Japan}. Such as The Tower of London, and the Metropolitan Museum in New York. And Mark’s personal antiques mentor in the 1970’s was Edward ‘Ted’ Dale, when he was Managing Director and chief auctioneer of one of the worlds leading auction houses, Bonhams of Knightsbridge, London.

Both Mark and David can usually be found here at the gallery and shop, most days, often buried under a pile of swords, pistols, books and bayonets. It is always the case of ‘take us as you find us’ as they say, but they are both always delighted to chat about everything swords, guns, books and history, with no purchase necessary!

In memoriam

For over 30 years we had the enjoyment of the company of the late Christopher Fox as our consultant on Nihonto. A great friend to us all, and one of the most modest and knowledgable experts on Japanese swords in England. Also he was a member of the leading European sword appreciation society for several decades, and a student and instructor of the martial art of Iaido for four decades. The second in command so to speak of sensei Roald Knutsen, one of the worlds greatest experts and author on samurai polearms. {Chris was also a whizz on all things of a military nature from 20th century Germany.}

Did you know? the most valuable sword in the world today is a samurai sword, it belongs to an investment fund and has appeared illustrated in the Forbes 400 magazine. It is valued by them at $100 million, it is a tachi from the late Koto period 16th century and unsigned. Its blade is grey and now has no original polish remaining. read more

Price

on

Request

A Beautiful And Rare American Revolutionary War Period Large Boxlock Action Double Cannon Barrelled Flintlock Volley Gun Pistol, Silver Scroll Inlaid Butt

A renown ‘Queen Anne’ style volley gun. A fascinating and most rare breech loading piece, with twin over and under turn-off cannon barrels, that is able to fire as a volley gun, with both barrels simultaneously, or, one after the other, using a unique sliding trigger guard that opens or covers one of the ignition pans as is required. 50 bore, double barrelled large over and under flintlock boxlock pistol, c1770,” the muzzles starred for a barrel key, with two separate pans beneath a single frizzen, the sliding cover of one pan operated by the sliding trigger guard, the frame retaining traces of etching, the rounded flat sided walnut butt inlaid with silver scrolls and wavy lines. World famous English gunsmith from London Durs Egg was renown for making incredibly similar rare twin cannon barrelled pistols, also with unusual covered pan actions. No proofs. Discussing with Howard Blackmore of the Tower Armouries some decades ago, the non-proved 18th century guns were often for the American export market where proofing was not required. Queen Anne pistols are characterized by the fact that the breech and the trigger plate are forged in one piece with the lock plate, foreshadowing by over 100 years the so-called "action" of a modern weapon. With the typical 'Queen Anne' pistol the barrel unscrews with a barrel key or wrench just ahead of the chamber where the powder and ball are placed when the pistol is loaded. The chamber is long and narrow with a cup at the top shaped to fit the bullet (a round lead ball). The user can quickly fill the chamber with black powder and put a bullet on top; the barrel is then replaced, sealing the bullet between its cup and the breech end of the barrel.

The bullet is larger than the barrel, so the breech is tapered to compress the ball as it moves forward at the moment of firing to tightly fit the bore. High gas pressure is developed behind the bullet before it is forced into the barrel, thus achieving considerably higher muzzle velocity and power than with a muzzle loader. The barrel was often rifled, which improves accuracy. The system also avoids the need for wadding or a ramrod during loading. It was not hugely successful as a military weapon at the time because in the heat of battle the separate barrel could be dropped during loading. The greatest popularity of the Queen Anne was as an effective self-defense weapon. They could be highly decorated with silver to suit the tastes of the very wealthy. But in the case of a double barrel they were especially popular, but most expensive, in fact considerably more than a pair of single barrelled versions.

The firing action functions on a single cock, wear overall to stock and steel as usual due to age. Pistol 10.5" long overall, read more

3250.00 GBP

Pair of Magnificent, Royal Quality, Superb, French, Solid Silver Mounted 18th Century 'Parisian' Saddle & Duelling Pistols, Last Used in Combat At Waterloo, Bespoke Made by Maitre Kettinis, Arquebusier a Paris

Just arrived, part of our stunning Waterloo collection display. This is truly magnificent pair of highest rank of officer's saddle cum duelling pistols, used by a family descendant of the original owner, who used them in the Seven Years War and American Revolutionary era, and then by his descendant who served in the Napoleonic wars, Peninsular and Waterloo.

The pair of solid silver mounted long, saddle pistols with gold inlaid barrels, bespoke hand made by their Parisian master gunsmith, for their original, nobleman or prince, owner by Maitre Lambert Kettenis of Paris, and we have a photo of an original 18th century document from the office of the Directoire General des Archives, in France, with his name listed for probate in 1770. From the era and quality of royal grade pistols as the world famous Lafayette-Washington-Jackson pistols. Wonderful carved walnut stocks with rococo flower embellishments solid silver furniture including long eared butt caps, sideplate chisselled with stands of arms, chisselled silver mounted trigger guards hallmarked and barrel ramrod pipes, all sublimely engraved and chiselled with wonderful detailing of florid designs, and stands of arms, fine steel locks, with flintlock later adapted percussion actions, engraved with the name of Maitre L Kettenis.

Very similar to the French Lafayette-Washington pistols made in circa 1775. While of great historical importance, those pistols were also very fine pieces indeed, just like ours, but they had less expensive steel mounts, whereas these are solid silver, but both are typical of the finest gunsmith workmanship of the day. The Washington pistols were purchased by the Marquis de Lafayette, and were presented by him, to General George Washington, during the Revolutionary War in 1778. They, just as these pistols, are finest examples of eighteenth-century sidearms with exquisite carved and engraved Rococo embellishments. The Washington Lafayette pair are likely the best documented pistols of their kind once belonging to Washington. The Washington pair sold in 2002 for just under $2,000,000.00. King George III, acquired another pair of pistols most similar to these and Washingtons, and they are the collection of the Royal Family of England at Windsor Castle. George III ascended the throne in 1760. As with all our antique guns, no license is required as they are all unrestricted antique collectables

These pair of pistols must’ve been handmade for an prince or nobleman of highest status and rank, such as colonel or general, at the time of the Anglo French wars in America in the 1760s and likely used continually through the American Revolutionary War period and into the Napoleonic era. After which they were ‘convert silex’ from flintlock, in order to enhance their performance in poor and wet weather. A system much promoted by Napoleon himself, in fact he made entreaties to the Reverend Forsyth of Scotland, a well known earliest designer of the silex system, to become Napoleon’s consultant to his armoury in Versailles, an offer which Forsyth refused due his loyalty to the British crown.

Flintlocks could not function in damp or rainy conditions, but the system silex surmounted this problem, and enabled such converted pistols for their more effective and efficient use for at least for a further 20 years.

Picture in the gallery is of a surviving register in a French National archive of the official record of the will of Kettenis, Lambert, Maître arquebusier, it further names his wife, as femme Louise Elisabeth. His will was probated 1770-07-10.

This stunning pair are in superb condition for age, and we have left them just ‘as-is’, only one hammer cocks and locks perfectly, yet both actions have superbly crisp and strong main springs, with one small nipple top a/f.. read more

9950.00 GBP

A Simply Stunningly Mounted Handachi Katana Shinto Period Circa 1650

Shakudo and gold fittings with a pair of top quality gold and shakudo tiger menuki under the orginal Edo period silk wrap tsukaito, over black giant rayskin, samegawa. Bulls blood ishime stone finish lacquer, sukashi mokko tsuba in the form of clan mon [crests]. The sword is mounted in a beautiful matching suite of original Edo period gold and shakudo handachi fittings, with kabutogane, shibabiki, and ishizuki. Han-dachi originally appeared during the Muromachi period when there was a transition taking place from Tachi to katana. The sword was being worn more and more edge up when on foot, but edge down on horseback as it had always been. The handachi is a response to the need to be worn in either style. The samurai were roughly the equivalent of feudal knights. Employed by the shogun or daimyo, they were members of hereditary warrior class that followed a strict "code" that defined their clothes, armour and behaviour on the battlefield. But unlike most medieval knights, samurai warriors could read and they were well versed in Japanese art, literature and poetry.

Samurai endured for almost 700 years, from 1185 to 1867. Samurai families were considered the elite. They made up only about six percent of the population and included daimyo and the loyal soldiers who fought under them. Samurai means one who serves."

Samurai were expected to be both fierce warriors and lovers of art, a dichotomy summed up by the Japanese concepts of bu [to stop the spear] exanding into bushido (the way of life of the warrior) and bun (the artistic, intellectual and spiritual side of the samurai). Originally conceived as away of dignifying raw military power, the two concepts were synthesized in feudal Japan and later became a key feature of Japanese culture and morality. The quintessential samurai was Miyamoto Musashi, a legendary early Edo-period swordsman who reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday and was also a painting master. Members of a hierarchal class or caste, samurai were the sons of samurai and they were taught from an early age to unquestionably obey their mother, father and daimyo. When they grew older they were trained by Zen Buddhist masters in meditation and the Zen concepts of impermanence and harmony with nature. The were also taught about painting, calligraphy, nature poetry, mythological literature, flower arranging, and the tea ceremony.

As part of their military training, samurai were taught to sleep with their right arm underneath them so if they were attacked in the middle of the night and their the left arm was cut off the could still fight with their right arm. Samurai that tossed and turned at night were cured of the habit by having two knives placed on either side of their pillow.

Samurai have been describes as "the most strictly trained human instruments of war to have existed." They were expected to be proficient in the martial arts of aikido and kendo as well as swordsmanship and archery---the traditional methods of samurai warfare---which were viewed not so much as skills but as art forms that flowed from natural forces that harmonized with nature.

An individual didn't become a full-fledged samurai until he wandered around the countryside as begging pilgrim for a couple of years to learn humility. When this was completed they achieved samurai status and receives a salary from his daimyo paid from taxes (usually rice) raised from the local populace. Swords in Japan have long been symbols of power and honour and seen as works of art. Often times swordsmiths were more famous than the people who used them. The blade shows a dramatic sophisticated suguha hamon [straight] with a few natural age pit marks. As with all our items it comes complete with our certificate of authenticity.

Overall 39.75 inches long, blade tsuba to tip 25.65 inches long read more

7450.00 GBP

A Most Scarce, Original, Early 17th Century English Civil War Infantry Musketeer's or Pikeman's Comb Morion Helmet

Used from the 30 years war and into the English Civil War, as the pattern used by both musketeers and pikemen. The musket soon became the dominant infantry weapon during the Civil War. Musketeers could move and react faster than the Pikeman in their heavy armour. They were easier to train and the musket could kill and maim the enemy up to 200 paces away. If you could keep your enemy at this distance you didn't have to close to hand to hand combat.

The role of musketeer is more technical than that of the pikeman. As a musketeer within the regiment, you will be using a replica period matchlock musket, and when appropriate, carrying a set of bandoliers, holding the required amount of gunpowder to fire it.

The pikeman of the English Civil War. A pike was a wooden pole up to 18 feet long with a sharp metal spike. Its name comes from the French piquer, meaning ‘pierce’. Although the pike evolved in the Middle Ages, pike blocks more closely resembled Ancient Greek phalanxes.

It was considered to be a more noble and traditional weapon than the musket – a weapon for gentlemen that needed strength, skill, and training to master and nerves of steel to fight with. Pike blocks could consist of up to 200 men and would form up in the centre of the line of battle; they could either protect musketeers from cavalry attack or be used as huge offensive infantry formations that would edge towards each other, their pikes levelled at ‘the charge’ before engaging in ‘push of pike’, where they would try and break the enemy’s formation.

At the beginning of the English Civil Wars, armies would have roughly one pikeman for every two musketeers. By the 1650s, this was closer to one to four or five and, as muskets became more effective and use of the bayonette became widespread, the pike become obsolete and the regular use of pikes ended with the beginning of the 18th Century. read more

2250.00 GBP

A Stunning Mid 18th Century Ship's Captain Brass Cannon Barrel Pistol with a Silver Escutchon of the Goddess Minerva Adorned With Her Dolphin Helmet & Fishscale Armour

Blunderbuss pistol all brass cannon barrel, and action, beautifully engraved. Made by Hadley circa 1750, with large silver escutcheon engraved with the profile head of Minerva.

Minerva, whose dolphin helmeted face is depicted is the Roman goddess of wisdom, justice, law, victory, and the sponsor of arts, trade, and strategy. Minerva is not a patron of violence such as Mars, but of strategic warfare.

The ‘Queen Anne’ style pistol is distinctive in that it does not have a ramrod. The barrel of the pistol unscrews and allows it to be loaded from the rear and near the touch hole at the breech of the barrel. These pistols were originally made in flintlock.

The Queen Anne pistols were very popular and were made in a variety of calibres, usually about 38 to 50 bore. Boot pistols, Holster pistols, pocket pistols and Sea Service pistols were all made in the 'Queen Anne' style. This type is known as a Queen Anne pistol because it was during her reign that it became popular (although it was actually introduced in the reign of King William III).

Here are some of the specific reasons why people enjoy collecting antique pistols:

Historical significance: Antique pistols are stunning relics of a bygone era, and they can provide insights into the history of warfare, technology, and culture. For example, a collector might be interested in owning a type of pistol that was used in a famous battle or that was carried by a famous historical figure.

Craftsmanship: Antique pistols are often works of art in their own right. Many early gunsmiths were highly skilled artisans, and their creations can be extraordinarily beautiful. Collectors might appreciate the intricate engraving, fine inlays, and other decorative elements that are found on many antique pistols.

Aesthetic beauty: Antique pistols can be simply stunning. Their elegant lines and graceful curves can be a thing of beauty. Collectors might enjoy admiring the form and function of these antique weapons.

Rarity and uniqueness: Some antique pistols are quite rare, and collectors might enjoy the challenge of finding and acquiring them. Others might be interested in owning a pistol that is unique in some way, such as a prototype or a custom-made piece.

Investment value: Antique pistols can also be valuable long term investments. The value of some antique pistols has appreciated significantly over the years. Collectors might enjoy the potential for profit, in addition to the other pleasures of collecting, but that should never be the ultimate goal, enjoyment must always be the leading factor of collecting.

No matter what their reasons, collectors of antique pistols find enjoyment in their hobby. They appreciate the history, craftsmanship, beauty, and rarity of these unique pieces.

In addition to the above, here is yet another reason why people enjoy collecting antique pistols:

Education: Learning about the history and technology of antique pistols can be a thoroughly rewarding experience. Collectors can learn about the different types of pistols that have been made over the centuries, how they worked, and how they were used.

Excellent condition overall, good tight and crisp action, old small split in stock, overall 12.5 inches long read more

2950.00 GBP

A Magnificent Tower of London Armoury 1801 Pattern 'Battle of Trafalgar 1805 Issue' Royal Navy Issue, British Sea Service Pistol From Admiral Lord Nelson's Navy. Long 12 inch Barrel

Probably one of the best examples of a Royal Navy Sea Service pistol that we have seen. Profusely struck with ordnance and inspectors marks, dated 1805, and numbered for the ship's gun rack, 25.

Fantastic patina to the stock. The King George IIIrd issue British Royal Naval Sea Service pistol has always been the most desirable and valuable pistol sought by collectors, but this example is truly exceptional.

Exactly as issued and used by all the British Ship's-of-the-Line, at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

Such as;

HMS Victory,

HMS Temeraire,

HMS Dreadnought,

HMS Revenge,

HMS Agamemnon,

HMS Colossus

HMS Leviathan &

HMS Achilles.

Some of the most magnificent ships, manned by the finest crews, that have ever sailed the seven seas.

Battle of Trafalgar, (October 21, 1805), naval engagement of the Napoleonic Wars, which established British naval supremacy for more than 100 years; it was fought west of Cape Trafalgar, Spain, between Cádiz and the Strait of Gibraltar. A fleet of 33 ships (18 French and 15 Spanish) under Admiral Pierre de Villeneuve fought a British fleet of 27 ships under Admiral Horatio Nelson.

At the end of September 1805, Villeneuve had received orders to leave Cádiz and land troops at Naples to support the French campaign in southern Italy. On October 19–20 his fleet slipped out of Cádiz, hoping to get into the Mediterranean Sea without giving battle. Nelson caught him off Cape Trafalgar on October 21.

Villeneuve ordered his fleet to form a single line heading north, and Nelson ordered his fleet to form two squadrons and attack Villeneuve’s line from the west, at right angles. By noon the larger squadron, led by Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood in the Royal Sovereign, had engaged the rear (south) 16 ships of the French-Spanish line. At 11:50 AM Nelson, in the Victory, signaled his famous message: “England expects that every man will do his duty.” Then his squadron, with 12 ships, attacked the van and centre of Villeneuve’s line, which included Villeneuve in the Bucentaure. The majority of Nelson’s squadron broke through and shattered Villeneuve’s lines in the pell-mell battle. Six of the leading French and Spanish ships, under Admiral Pierre Dumanoir, were ignored in the first attack and about 3:30 PM were able to turn about to aid those behind. But Dumanoir’s weak counterattack failed and was driven off. Collingwood completed the destruction of the rear, and the battle ended about 5:00 PM. Villeneuve himself was captured, and his fleet lost 19 or 20 ships—which were surrendered to the British—and 14,000 men, of whom half were prisoners of war. Nelson was mortally wounded by a sniper, but when he died at 4:30 PM he was certain of his complete victory. About 1,500 British seamen were killed or wounded, but no British ships were lost. Trafalgar shattered forever Napoleon’s plans to invade England.

Obviously this arm has signs of combat use and the stock has minor dings. But when taken into consideration its service use, it is of little consequence compared to it's condition, which is truly exceptional, with, incredibly, absolutely not a trace of rust or corrosion on the more usually heavily pitted, steel, lock and barrel.

It still has it's original 12" barrel, which is very scarce as the barrels were shortened by official order, to 9", before the Napoleonic wars.

In its working life its belt hook has been removed. read more

3450.00 GBP

A Beautiful, Shinto Period, Handachi Mounted Samurai Katana. Fitted With All Original Edo Mounts. Showing Great Quality, Shibui {Quietly Reserved} And Without Undue Extravagance. An Impressive Sword With Incredible & Elegant Lines & Curvature

Worthy of any museum grade collection.

All original, fabulous, Edo period koshirae sword fittings and mounts, a fully matching suite of han dachi mounts semi tachi form inlaid in pure gold arabesques on iron, Higo style. The blade is in beautiful polish showing a spectacularly undulating regular gunome hamon. The tsuka is bound in blue silk and the saya has its original old Edo ishime lacquer, the tsuba is a mokko form iron plate inlaid with a stylized dragon in gold to match the fittings.

Han-dachi originally appeared during the Muromachi period when there was a transition taking place from tachi to katana. The sword was being worn more and more edge up when on foot, but edge down on horseback as it had always been. The handachi is a response to the need to be worn in either style. The samurai were roughly the equivalent of feudal knights. Employed by the shogun or daimyo, they were members of hereditary warrior class that followed a strict "code" that defined their clothes, armour and behaviour on the battlefield. But unlike most medieval knights, samurai warriors could read and they were well versed in Japanese art, literature and poetry.

Samurai endured for almost 700 years, from 1185 to 1867. Samurai families were considered the elite. They made up only about six percent of the population and included daimyo and the loyal soldiers who fought under them. Samurai means "one who serves."

Samurai were expected to be both fierce warriors and lovers of art, a dichotomy summed up by the Japanese concepts of bu to stop the spear exanding into bushido (the way of life of the warrior) and bun (the artistic, intellectual and spiritual side of the samurai). Originally conceived as away of dignifying raw military power, the two concepts were synthesized in feudal Japan and later became a key feature of Japanese culture and morality.

The quintessential samurai was Miyamoto Musashi, a legendary early Edo-period swordsman who reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday and was also a painting master. Members of a hierarchal class or caste, samurai were the sons of samurai and they were taught from an early age to unquestionably obey their mother, father and daimyo. When they grew older they may be trained by Zen Buddhist masters in meditation and the Zen concepts of impermanence and harmony with nature. The were also taught about painting, calligraphy, nature poetry, mythological literature, flower arranging, and the tea ceremony.

As part of their military training, apparently, samurai were taught to sleep with their right arm underneath them so if they were attacked in the middle of the night and their the left arm was cut off the could still fight with their right arm. Samurai that tossed and turned at night may be cured of the habit by having two knives placed on either side of their pillow.

Samurai have been describes as "the most strictly trained human instruments of war to have existed."

They were expected to be proficient in the martial arts of aikido and kendo as well as swordsmanship and archery---the traditional methods of samurai warfare---which were viewed not so much as skills but as art forms that flowed from natural forces that harmonized with nature.

It can also be said an individual didn't become a full-fledged samurai until he wandered around the countryside as begging pilgrim for a couple of years to learn humility. How accurate this was is dependant on the urgencies of war.

When this was completed they achieved samurai status and receives a salary from his daimyo paid from taxes (usually rice) raised from the local populace.

Swords in Japan have long been symbols of power and honour and seen as works of art. Often times swordsmiths were more famous than the people who used them.

As with all our items it comes complete with our certificate of authenticity. Blade tsuba to tip 27.5 inches, overall in saya 38.5 read more

7950.00 GBP