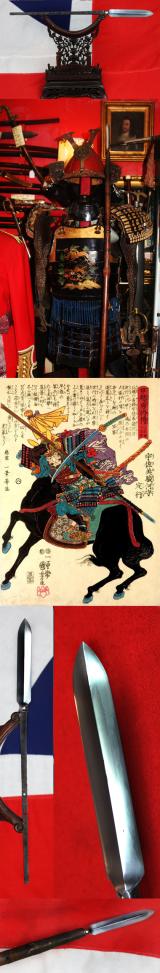

Japanese

The Lanes Armoury Probably The Largest Online Militaria Website in the World, After Over 100 Years of Brighton Trading, &, The 24th Anniversary of Our Best Antique & Collectables Shop in Britain Award

In this very special anniversary year of 80 years since VE Day in 1945.

Presented by MILLER'S Antiques Guide, THE BBC, HOMES & ANTIQUES MAGAZINE in 2001.

Five years ago we were approached by a most historically enthusiastic young person studying at Sussex University who asked if they could research through our archive to complete a 'paper' based on us as one of the oldest remaining Sussex family business's.

It resulted in some remarkable statistics, that we thought we would share with our regulars, for those that have interest. The research only included the types of items that we regularly buy, sell and export today, with general antiques, furniture, porcelain, clocks, silver and works of art excluded, as we haven't been devoted to that side of the trade since selling our antique export shipping companies in 1992.

In over 100 years of shop keeping in Brighton, at the time of his research, 80 of them pre-internet, apparently, we have likely sold over 200,000 books, {vintage and antique books were, and are, our largest selling single item}, 135,000 medals & badges, over 95,000 worldwide swords, knives and bayonets, over 32,000 Japanese samurai swords {for example, around 28 years ago we bought over 150 Japanese WW2 NCO swords in one vast lot, from the grandson of a WW2 British military surplus dealer, who acquired them for scrap in 1946 from the War Dept}. We have sold and exported,, apparently over 28,500 helmets of all origins and types, 27,000 pistols and muskets of all countries, at least 2450 suits of armour, European, British or Japanese, and over 1,500 cannon, both signal and full sized. Believe it or not, apparently, according to their research and calculations, these are potentially conservative figures, and the actual figure could indeed be much higher.

So, please enjoy our historical website, and remember, every thing you see is available and for sale, we try to never keep our webstore filled with past 'sold' items.

Being part of the centre of the historic Brighton Lanes, anything up 2,000 to 3,000 people, will visit us here most days {especially on Saturdays} winter and summer, rain or shine.

We issue our unique, certificate of authenticity, with every single item purchased, and in regards to our Japanese items, both weapons and fittings etc. our ability to do this is based on well over a century of experience, as probably the largest military antiques dealers in Europe. We detail within our certificates, their beauty, approximate age, style, and the feature of their fittings and mounts, and their potential position and status in Japanese samurai history. We will detail the translations, if known, of the kanji (names) chisselled upon the nakago of swords, under their hilt bindings, but purely for information only, although the myth persists that all Japanese master smiths signed their swords, historically, and factually, it is likely less than 30% of samurai blades were in fact ever signed. This fact is certainly found, and confirmed by us to be the case, due to our family’s 100 plus years experience. For example, it is said one of the greatest master smiths who ever lived, Masamune, was, apparently, most reluctant to ever sign his swords. Although this must be relative speculation, as so very few of his swords have been recognised to still exist

Our Certificates of Authenticity are our own unique version of a lifetime guarantee, based on our expertise honed over 100 years, containing a detailed description of any item purchased from our stock. In relation to our samurai weapons, the description with be a combination of our opinion of its style, approximate age and beauty, and for our Japanese samurai swords in particular, that it is an ‘original’, samurai sword, made and used by samurai, both ancient and vintage, within Japan, over the past 700 years, up to the last samurai period in the Meiji era of 1868, as well as up to 1945, if it is a military mounted shingunto sword.

Photos 4 and 5 are part of an editorial in Art and Antiques Weekly Magazine, featuring the story so far { in 1975} of the partner’s former family antiques export company, one of the largest in the world at that time. In 1992 Mark and David retired from the mass wholesale export market and morphed their business into the becoming one of the largest dedicated ‘military antiques’ businesses instead, both of their true passions. read more

Price

on

Request

A Wonderful 500 Year Old Koto Period Samurai 'Dragon' Wakizashi Samurai Short Sword, Another Absolute Beauty From Our latest collection

Based entirely around the legendary Japanese dragon, Bearing the dragon on all of its fittings and mounts including its kozuka utility knife. All of the fittings are original Edo period, of very nice quality the dragon tsuba is iron with gold highlights, of a chiselled takebori dragon signed by a very good tsuba maker, Kinai.

One has to bear in mind this tanto has been used by numerous samurai over more than a dozen generations, since the era, in England, when King Henry the VIIIth was a child.

The tsuka is superb and has its original, Edo period, beautiful mid blue silk binding, that is patterned damask silk with a clan mon design theme, with two very old, small surface moth marks. It is a very rare, and most infrequently seen form of deluxe quality tsuka-ito, that is wrapped over black samegawa giant ray-skin, over the gold dragon menuki. The fuchi is fine Soten school, of a pure gold decor takebori dragon, over a shakudo Nanak o ground. The kashira is hand carved and polished black buffalo horn.

The saya has its incredible Edo period urushi lacquer in a stippled ishime stone finish. and within its saya pocket is the kozuka utility knife, with a sinchu handle, decorated with a takebori carved sea dragon in crashing waves, the saya bears a shakudo mount of a deep and crisp, rare type takebori mythical flying sea dragon with a fishtail. The blade is in super and beautiful polish, showing a delightful light notare, based on suguha, hamon.

The original Edo period urushi lacquer on the saya is in simply excellent condition for age and shows most elegant patterning, it reveals within that intricacy the finest craftsmanship and beauty worthy of a master of the art of urushi decor. Japanese lacquer, or urushi, is a transformative and highly prized material that has traced it origins, and been refined, for over several thousands of years.

Cherished for its infinite versatility, urushi is a distinctive art form that has spread across all facets of Japanese culture from the tea ceremony to the saya scabbards of samurai swords

Japanese artists created their own style and perfected the art of decorated lacquerware during the 8th century. Japanese lacquer skills reached its peak as early as the twelfth century, at the end of the Heian period (794-1185). This skill was passed on from father to son and from master to apprentice.

The varnish used in Japanese lacquer is made from the sap of the urushi tree, also known as the lacquer tree or the Japanese varnish tree (Rhus vernacifera), which mainly grows in Japan and China, as well as Southeast Asia. Japanese lacquer, 漆 urushi, is made from the sap of the lacquer tree. The tree must be tapped carefully, as in its raw form the liquid is poisonous to the touch, and even breathing in the fumes can be dangerous. But people in Japan have been working with this material for many millennia, so there has been time to refine the technique!

Flowing from incisions made in the bark, the sap, or raw lacquer is a viscous greyish-white juice. The harvesting of the resin can only be done in very small quantities.

Three to five years after being harvested, the resin is treated to make an extremely resistant, honey-textured lacquer. After filtering, homogenization and dehydration, the sap becomes transparent and can be tinted in black, red, yellow, green or brown.

We are very privileged to be the UK’s premier original military antiques gallery and website, and to be able to consistently, continually, and regularly, offer the finest original collectors items in our shop for over 100 years read more

4750.00 GBP

A Very Fine & Beautiful Handachi Katana Dated 1539 signed Bizen Kuni Osafune ju Tsuguiye

Just under 500 years old, and a delight to observe the wonderful curvature to the blade. It possesses a very long signature by the smith on the nakago. It has all original Edo period mounts fittings and saya, with original saya intricately patterned urushi lacquer. Typical Edo handachi mounts with a beautiful iron tsuba with gold onlay of prunus and grasses. It has a very active hamon on the stunning blade and it’s all original Edo tsukaito binding to the hilt, now somewhat pleasingly colour faded in part and usual signs of combat use age appropriate wear as to be expected.

The samurai were roughly the equivalent of feudal knights. Employed by the shogun or daimyo, they were members of hereditary warrior class that followed a strict "code" that defined their clothes, armour and behaviour on the battlefield. But unlike most medieval knights, samurai warriors could read and they were well versed in Japanese art, literature and poetry.

Samurai endured for almost 700 years, from 1185 to 1867. Samurai families were considered the elite. They made up only about six percent of the population and included daimyo and the loyal soldiers who fought under them. Samurai means one who serves."

Samurai were expected to be both fierce warriors and lovers of art, a dichotomy summed up by the Japanese concepts of bu to stop the spear expanding into bushido (the way of life of the warrior) and bun (the artistic, intellectual and spiritual side of the samurai). Originally conceived as away of dignifying raw military power, the two concepts were synthesised in feudal Japan and later became a key feature of Japanese culture and morality.The quintessential samurai was Miyamoto Musashi, a legendary early Edo-period swordsman who reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday and was also a painting master. Members of a hierarchal class or caste, samurai were the sons of samurai and they were taught from an early age to unquestionably obey their mother, father and daimyo. When they grew older they may be trained by Zen Buddhist masters in meditation and the Zen concepts of impermanence and harmony with nature. The were also taught about painting, calligraphy, nature poetry, mythological literature, flower arranging, and the tea ceremony.

it has been said that part of their military training, samurai were taught to sleep with their right arm underneath them so if they were attacked in the middle of the night and their the left arm was cut off the could still fight with their right arm. Samurai that tossed and turned at night were cured of the habit by having two knives placed on either side of their pillow.

Samurai have been describes as "the most strictly trained human instruments of war to have existed." They were expected to be proficient in the martial arts of aikido and kendo as well as swordsmanship and archery---the traditional methods of samurai warfare---which were viewed not so much as skills but as art forms that flowed from natural forces that harmonized with nature.

Some samurai, it has been claimed, didn't become a full-fledged samurai until he wandered around the countryside as begging pilgrim for a couple of years to learn humility. When this was completed they achieved samurai status and receives a salary from his daimyo paid from taxes (usually rice) raised from the local populace.

Japanese lacquer, or urushi, is a transformative and highly prized material that has been refined for over 7000 years.

Cherished for its infinite versatility, urushi is a distinctive art form that has spread across all facets of Japanese culture from the tea ceremony to the saya scabbards of samurai swords

Japanese artists created their own style and perfected the art of decorated lacquerware during the 8th century. Japanese lacquer skills reached its peak as early as the twelfth century, at the end of the Heian period (794-1185). This skill was passed on from father to son and from master to apprentice.

Some provinces of Japan were famous for their contribution to this art: the province of Edo (later Tokyo), for example, produced the most beautiful lacquered pieces from the 17th to the 18th centuries. Lords and shoguns privately employed lacquerers to produce decorated samurai sword saya and also ceremonial and decorative objects for their homes and palaces.

27.25 inch blade tsuba to tip.

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery read more

8850.00 GBP

A Beautiful Antique Edo Period Wakizashi Samurai Short Sword, With a Fabulous Quality Botanical Shakudo Gold and Silver Takebori Mounts & Tsuba

Circa 1680. A stunning antique shinto wakazashi samurai sword, its blade and fittings saya etc. have been almost completely untouched since its arrival in England around 150 years ago. All original Edo period fittings with one mekugi-ana, midare hamon, fully bound tsuka with shakudo fuchi-kashira decorated with flowers and tendrils in gold, shakudo and gold floral menuki, mokko-shaped iron tsuba decorated with silver and gold takebori foliage, in its beautiful black stippled lacquer saya complete with a super shakudo kodzukatana utility knife decorated with a takebori figure of a sage, possibly Tenaga from Japanese folklore, and a dog on a lead. Fabulous faultless blade showing a superb undulating hamon.

Wakizashi have been in use as far back as the 15th or 16th century. The wakizashi was used as a backup or auxiliary sword; it was also used for close quarters fighting, and also to behead a defeated opponent and sometimes to commit ritual suicide. The wakizashi was one of several short swords available for use by samurai including the yoroi toshi, the chisa-katana and the tanto. The term wakizashi did not originally specify swords of any official blade length and was an abbreviation of "wakizashi no katana" ("sword thrust at one's side"); the term was applied to companion swords of all sizes. It was not until the Edo period in 1638 when the rulers of Japan tried to regulate the types of swords and the social groups which were allowed to wear them that the lengths of katana and wakizashi were officially set.

There are many reasons why people enjoy collecting swords. Some people are drawn to the beauty and craftsmanship of swords, while others appreciate their historical and cultural significance. Swords can also be a symbol of power and strength, and some collectors find enjoyment in the challenge of acquiring rare or valuable swords.

One of the greatest joys of sword collecting is the opportunity to learn about the history and culture of different civilisations. Swords have been used by warriors for millennia, and each culture has developed its own unique sword designs and traditions. By studying swords, collectors can gain a deeper understanding of the people who made and used them.

Another joy of sword collecting is the sheer variety of swords that are available. There are swords in our gallery from all over the world and from every period of history. Collectors can choose to specialize in a particular type of sword, such as Japanese katanas or medieval longswords, or they can collect a variety of swords from different cultures and time periods. No matter what your reasons for collecting swords, it is a hobby that can provide many years of enjoyment. Swords are beautiful, fascinating, and historically significant objects

Blade length 15.5 inches long

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery read more

4450.00 GBP

A Superb Samurai, Shinto Period, 350 Year Old, Ryo-Shinogi Yari Polearm Spear, Signed Bushu ju Shimosaka Fujiwara Kazunori, In Incredible Polish, Showing Fine Grain in the Hada and Wide Fine Suguha Hamon, With 12 'Notch' Tang

An Edo Period Samurai Horseman Ryo-Shinogi Yari Polearm on original haft, circa 1680. Fantastic polish showing amazing grain and deep hamon.

The blade is signed Bushu ju Shimosaka Fujiwara Kazunori, and bears 12 hand cut notches to the tang, which often represented the number of vanquished samurai by the yari weilding samurai, likely in a single battle

With original pole and iron foot mount ishizuki. Four sided double edged head. The mochi-yari, or "held spear", is a rather generic term for the shorter Japanese spear. It was especially useful to mounted Samurai. In mounted use, the spear was generally held with the right hand and the spear was pointed across the saddle to the soldiers left front corner.

The warrior's saddle was often specially designed with a hinged spear rest (yari-hasami) to help steady and control the spear's motion. The mochi-yari could also easily be used on foot and is known to have been used in castle defense. The martial art of wielding the yari is called sojutsu. A yari on it's pole can range in length from one metre to upwards of six metres (3.3 to 20 feet). The longer hafted versions were called omi no yari while shorter ones were known as mochi yari or tae yari. The longest hafted versions were carried by foot troops (ashigaru), while samurai usually carried a shorter hafted yari. Yari are believed to have been derived from Chinese spears, and while they were present in early Japan's history they did not become popular until the thirteenth century.The original warfare of the bushi was not a thing for "commoners"; it was a ritualized combat usually between two warriors who may challenge each other via horseback archery and sword duels. However, the attempted Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281 changed Japanese weaponry and warfare. The Mongol-employed Chinese and Korean footmen wielded long pikes, fought in tight formation, and moved in large units to stave off cavalry. Polearms (including naginata and yari) were of much greater military use than swords, due to their much greater range, their lesser weight per unit length (though overall a polearm would be fairly hefty), and their great piercing ability.

Swords in a full battle situation were therefore relegated to emergency sidearm status from the Heian through the Muromachi periods.

70.5 inches long overall,5.5 inches long blade, blade with tang overall 15 inches long read more

2120.00 GBP

An Ancient Koto Period Samurai Sword, Almost 600 Years old, From The Sengoku Jidai. A Handachi Mounted Katana, With Beautiful Deep Red Ishime Urushi Lacquer Saya, Contrasted With Spectacular Green-Blue Silk Tsuka-ito, Set With Hammered Silver Onlaid Mount

Han-dachi mounted samurai swords originally appeared during the Muromachi period when there was a transition taking place from tachi to katana. The sword was being worn more and more edge up when on foot, but edge down on horseback as it had always been.

From the Muramachi and Sengoku period. The blade was made almost 600 years ago, in or around 1450, and it is fully mounted in a fine suite of Edo period, all matching handachi koshirae sword mounts, fitted upon the saya and tsuka, with a very scarce highly decorative hand finish, of hammered silver over copper, to represent reflections of moonlight in silvery puddles of water. A most impressive, beautiful and statuesque sword. The blade shows a most stunning and active hamon. The tsuka has its traditional, stunning, blue-green silk wrap, over black samegawa {giant ray-skin}, with two takebori iron dragon menuki.

Han-dachi semi-tachi can be displayed on a tachi stand (tachi-kake), usually with the handle pointing down, blade up for respect/preservation (preventing sheath damage), and sometimes the signature (mei) facing outward, though it's a matter of preference and historical context.

The Sengoku period was initiated by the Ōnin War in 1467 which collapsed the feudal system of Japan under the Ashikaga Shogunate. The Sengoku period was named by Japanese historians after the similar but otherwise unrelated Warring States period of China. The era is beautifully depicted in Akira Kurowsawa’s films called Jidaigeki. The Sengoku Period (1467-1568 CE) was a lawless century-long era characterized by rising political instability, turmoil, and warlordism in Japan. During this period, field armies and soldiers rapidly rose in number, reaching tens of thousands of warriors. Many castles in Japan were built during the Sengoku Period as regional leaders and aristocrats alike competed for power and strong regional influence to win the favours of the higher-class Japanese at the time. Kurosawa’s film depiction of Macbeth, Throne of Blood, is set in this era of Japan’s feudal period. Original title 蜘蛛巣城, Kumonosu-jō, lit. 'The Castle of Spider's Web'

This then led to the creation of a more complex system within the military, the armoured infantry known as the ashigaru. Initiated by the collapse of the country’s feudal system during the 1467 Onin War, rival warlords or daimyō, continued to struggle to gain control of Japan until its reunification under Japan’s three “Great Unifiers” –– Nagoya Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu Tokugawa –– thus, bringing the war-stricken era to an end in the siege of Osaka

The handachi is a response to the need to be worn in either style. The samurai were roughly the equivalent of feudal knights. Employed by the shogun or daimyo, they were members of hereditary warrior class that followed a strict "code" that defined their clothes, armour and behaviour on the battlefield. But unlike most medieval knights, samurai warriors could read and they were well versed in Japanese art, literature and poetry.

Samurai endured for almost 700 years, from 1185 to 1867. Samurai families were considered the elite. They made up only about six percent of the population and included daimyo and the loyal soldiers who fought under them. Samurai means one who serves."

Samurai were expected to be both fierce warriors and lovers of art, a dichotomy summed up by the Japanese concepts of bu, to stop the spear, expanding into bushido (the way of life of the warrior) and bun (the artistic, intellectual and spiritual side of the samurai). Originally conceived as away of dignifying raw military power, the two concepts were synthesized in feudal Japan and later became a key feature of Japanese culture and morality.

The quintessential samurai was Miyamoto Musashi, a legendary early Edo-period swordsman who reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday and was also a painting master.

The name katana derives from two old Japanese written characters or symbols: kata, meaning side, and na, or edge. Thus a katana is a single-edged sword that has had few rivals in the annals of war, either in the East or the West. Because the sword was the main battle weapon of Japan's knightly man-at-arms (although spears and bows were also carried), an entire martial art grew up around learning how to use it. This was kenjutsu, the art of sword fighting, or kendo in its modern, non-warlike incarnation. The importance of studying kenjutsu and the other martial arts such as kyujutsu, the art of the bow, was so critical to the samurai a very real matter of life or death that Miyamoto Musashi, most renowned of all swordsmen, warned in his classic The Book of Five Rings: The science of martial arts for warriors requires construction of various weapons and understanding the properties of the weapons. A member of a warrior family who does not learn to use weapons and understand the specific advantages of each weapon would seem to be somewhat uncultivated. European knights and Japanese samurai have some interesting similarities. Both groups rode horses and wore armour. Both came from a wealthy upper class. And both were trained to follow strict codes of moral behaviour. In Europe, these ideals were called chivalry; the samurai code was called Bushido, "the way of the warrior." The rules of chivalry and Bushido both emphasize honour, self-control, loyalty, bravery, and military training.

Samurai have been describes as "the most strictly trained human instruments of war to have existed." They were expected to be proficient in the martial arts of aikido and kendo as well as swordsmanship and archery---the traditional methods of samurai warfare---which were viewed not so much as skills but as art forms that flowed from natural forces that harmonized with nature.

Some samurai, it has been claimed, didn't become a full-fledged samurai until he wandered around the countryside as begging pilgrim for a couple of years to learn humility. When this was completed they achieved samurai status and receives a salary from his daimyo paid from taxes (usually rice) raised from the local populace.

40.5 inches long overall, blade 24.25 inches long read more

7450.00 GBP

A Most Handsome Shinto O-Tanto, Around 300 years Old Circa 1720 With a Most Impressive and Beautiful Large Blade Used As A Powerful Close-Combat Small Sword and Suitable as a Post Combat 'Head Cutter'

All original Edo period koshirae with a superb urushi lacquer saya of dark red with black angular overstriping and black banding at the top section, a fine takebori tetsu sayajiri mount, with a shakudo and gold kozuka utility knife with decoration of takebori zodiac animals, including a deer, rabbit, dragon, pony, snake, dog, rat, phoenix, hare etc.

It has very nice o-sukashi tetsu tsuba with a fine tsuka with Higo school fuchi kashira of iron decorated with takebori whirling clouds. The menuki under the tsuka ito are super quality of a pure gold sun and a shakudo crescent moon.

O-Tanto

The blade is long wide and very elegant with a great gunome hamon in beautiful polish. It has mighty strong thickness and size perfectly suitable as a samurai's close combat weapon, but also to double up, post combat, as a samurai's 'head cutter', if a kubikiri a solely dedicated head cutter, used by an attendant, was not available.

Samurai usually had to chop off their enemy’s head in order to prove to their daimyo or master that they actually killed the right person, not a woman or child.

Additionally collecting more heads meant getting more stipend and promotion.

However, after chopping the head, the samurai would always clean and put some light make up to the face to pay their respect to the dead person.

At the same time, every samurai also usually put incense within the inside their helmets knowing that they may get killed and their head's odour, due to the stress of battle, must not offend their killer.

In situations when the samurai did not have time to chop off the enemy’s head, they then used to cut off the upper lip (to distinguish if the head is male or female).

Tanto first began to appear in the Heian period, however these blades lacked artistic qualities and were purely weapons. In the Early Kamakura period high quality tanto with artistic qualities began to appear, and the famous Yoshimitsu (the greatest tanto maker in Japanese history) began his forging. Tanto production increased greatly around the Muromachi period and then dropped off in the Shinto period. Shinto period tanto are quite rare. Tanto were mostly carried by Samurai; commoners did not generally carry them. Women sometimes carried a small tanto called a kaiken in their obi for self defence.It was sometimes worn as the shoto in place of a wakizashi in a daisho, especially on the battlefield. Before the 16th century it was common for a Samurai to carry a tachi and a tanto as opposed to a katana and a wakizashi.

Blade 35.5 cm inches long, 3cm wide at the habaki, overall in the saya it is 51 cm long.

A solely dedicated kubikiri would normally have its cutting edge on the inside, and carried by attendants of high ranking samurai, but curiously the kubikiri would also be used for bonsai trimming.

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery read more

4950.00 GBP

Suit Of Original Edo Period Samurai Horserider Armour, With a Bajojingasa 馬上陣笠 Kabuto, A Samurai Horse Rider Battle Helmet. With Gold Maruni Tsuta Kamon. The Maruni Tsuta (丸に蔦) Kamon, Meaning "Japanese Ivy in a Ring". Matsunaga Family Crest in Kakuda

In our opinion there is no greater aesthetically attractive suit of antique original armour to compare to the Japanese samurai armour. One can see them displayed in some of the finest locations of interior decor in the world today.

For example, in the Hollywood movies such as the James Bond films many of the main protagonists in those films decorated their lush and extravagant billionaire properties with samurai armours. They can be so dramatic and beautiful and even the simplest example can look spectacular in any correct location with good lighting.

Original early Edo period.

Chain mail over silk Kote arm armour with plate Tekko hand armour. Fully laced and plate Sode shoulder armour Fully laced four panels of Haidate waist armour Fully laced Kasazuri thigh Armour, with Suneate. This armour is absolutely beautiful.

Japanese armour is thought to have evolved from the armour used in ancient China and Korea. Cuirasses and helmets were manufactured in Japan as early as the 4th century.Tanko, worn by foot soldiers and keiko, worn by horsemen were both pre-samurai types of early Japanese cuirass constructed from iron plates connected together by leather thongs.

Black urushi lacquer bajojingasa horseriders helmet 馬上陣笠 with superb mon, red lacquer interior with pad and cords but the cords outer silk has separated. With five leaf ivy in a ring mon of the Matsunaga clan.

Jingasa developed both in shape and decoration during the Edo era (1603-1867) and were a symbol of samurai culture. It was typically made of hardened lacquered leather, but also sometimes with iron. The jingasa would also commonly be marked with the mon of the lord or clan to help identify the warrior's side on a battlefield.

Samurai Bajo Jingasa (Riding Battle Hat) were worn mainly by officers a the end of the Sengoku period (1467-1615) and through the Edo period (1603-1868) and a little after. Traditionally a defensive helmet, they were allegedly first crafted from wood, leather, lacquered rawhide, then iron and later steel. The combination of these elements provided a good head protection against sword blows. The bajo-gasa jingasa are shaped like low round hills, believed to decrease wind resistance while on horseback. The inside is padded with a cushion liner secured by ribbons that would be tied and secured under the chin.

Cherished for its infinite versatility, urushi lacquer is a distinctive art form that has spread across all facets of Japanese culture from the tea ceremony to the saya scabbards of samurai swords Japanese artists created their own style and perfected the art of decorated lacquerware during the 8th century. Japanese lacquer skills reached its peak as early as the twelfth century, at the end of the Heian period (794-1185). This skill was passed on from father to son and from master to apprentice. The varnish used in Japanese lacquer is made from the sap of the urushi tree, also known as the lacquer tree or the Japanese varnish tree (Rhus vernacifera), which mainly grows in Japan and China, as well as Southeast Asia. Japanese lacquer, 漆 urushi, is made from the sap of the lacquer tree. The tree must be tapped carefully, as in its raw form the liquid is poisonous to the touch, and even breathing in the fumes can be dangerous. But people in Japan have been working with this material for many millennia, so there has been time to refine the technique! Overall in very nice condition for age with small lacquer wear marks.

During the Heian period 794 to 1185 the Japanese cuirass evolved into the more familiar style of armour worn by the samurai known as the dou or do. Japanese armour makers started to use leather (nerigawa) and lacquer was used to weather proof the armor parts. By the end of the Heian period the Japanese cuirass had arrived at the shape recognized as being distinctly samurai. Leather and or iron scales were used to construct samurai armours, with leather and eventually silk lace used to connect the individual scales (kozane) which these cuirasses were now being made from.

In the 16th century Japan began trading with Europe during what would become known as the Nanban trade. Samurai acquired European armour including the cuirass and comb morion which they modified and combined with domestic armour as it provided better protection from the newly introduced matchlock muskets known as Tanegashima. The introduction of the tanegashima by the Portuguese in 1543 changed the nature of warfare in Japan causing the Japanese armour makers to change the design of their armours from the centuries old lamellar armours to plate armour constructed from iron and steel plates which was called tosei gusoku (new armours).Bullet resistant armours were developed called tameshi gusoku or (bullet tested) allowing samurai to continue wearing their armour despite the use of firearms.

The era of warfare called the Sengoku period ended around 1600, Japan was united and entered the peaceful Edo period, samurai continued to use both plate and lamellar armour as a symbol of their status but traditional armours were no longer necessary for battles. During the Edo period light weight, portable and secret hidden armours became popular as there was still a need for personal protection. Civil strife, duels, assassinations, peasant revolts required the use of armours such as the kusari katabira (chain armour jacket) and armoured sleeves as well as other types of armour which could be worn under ordinary clothing.Edo period samurai were in charge of internal security and would wear various types of kusari gusoku (chain armour) and shin and arm protection as well as forehead protectors (hachi-gane).

Armour continued to be worn and used in Japan until the end of the samurai era (Meiji period) in the 1860s, with the last use of samurai armour happening in 1877 during the Satsuma Rebellion. The armour has some affixing loops lacking. Stand for photo display only not included. This armour has areas of worn and distressed lacquer and areas of cloth/material that are perished due to it's great age as would be expected, but the condition simply adds to its beauty and aesthetic quality, displaying its position within its combat use in Japanese samurai warfare. We would always recommend, in our subjective opinion, that original antique samurai armour looks its very best left completely as is, with all it wear and age imperfections left intact. read more

9950.00 GBP

A Beautiful Samurai Shinto Kirin Based Tanto Fabulous Signed Blade by Echizen Ju Yasutsugu

With an armour or even helmet piercing blade. The whole tanto is completely remarkable in that it is likely to have been completely untouched since the day it was made, it has all its original fittings from the Edo period including the tsukaito wrap on the hilt and the lacquer on the saya, the Saya is decorated with a stylised Kilin to match the fittings, the blade is stunning and shows fabulous deep choji hamon, this is a truly exceptional tanto,

The blade is extra thick at the base and shows its penetrating qualities and ability to cut through metal armour or even the iron plates of a helmet, this is a beautiful and remarkable tanto. The fuchigashira mounts are pure gold over shakudo of Kirin or Qilin, in deep takebori relief carving. The menuki are also Kirin, of shakedown inlaid with swirls of pure gold. The Kirin in Japanese, qilin (in Chinese: 麒麟; pinyin: qílín) is a mythical hooved chimerical creature known in Chinese and other East Asian cultures, said to appear with the imminent arrival or passing of a sage or illustrious ruler. It is a good omen thought to occasion prosperity or serenity. It is often depicted with what looks like fire all over its body. It is sometimes called the “Chinese unicorn” when compared with the Western unicorn. The Japanese kirin looked more like the Sin-you lion-like beast. Some later Japanese netsuke portray a Kirin that has wings that look like the Central Asian winged horse with horns or the Sphinx. Or they become increasingly dragon-like like Chinese Qilins.

The Kirin / Qilin can sometimes be depicted as having a single horn as in the Western tradition, or as having two horns. In modern Chinese the word for “unicorn” is 独角兽 “du jiao shou”, and a Qilin that is depicted as a unicorn, or 1-horned, is called “Du jiao Qilin” 独角麒麟 meaning “1-horned Qilin” or “Unicorn Qilin”. However, there are several kinds of Chinese mythical creatures which also are unicorns, not just Qilin. Qilin generally have Chinese dragon-like features.

Most notably their heads, eyes with thick eyelashes, manes that always flow upward and beards. The bodies are fully or partially scaled, though often shaped like an ox, deer or horse’s, and always with cloven hooves. In modern times, the depictions of Qilin have often fused with the Western concept of unicorns.

In legend, the Qilin became dragon-like and then tiger-like after their disappearance in East Asia and finally a stylised representation of the giraffe in Ming Dynasty. The identification of the Qilin with giraffes began after Zheng's voyage to East Africa according to recent scholarship. The modern Japanese word for giraffe is also kirin, which bears the same derived ideas. Shakudo is a billon of gold and copper (typically 4-10% gold, 96-90% copper) which can be treated to form an indigo/black patina resembling lacquer. Unpatinated shakudo Visually resembles bronze; the dark color is induced by applying and heating rokusho, a special patination formula.

Shakudo Was historically used in Japan to construct or decorate katana fittings such as tsuba, menuki, and kozuka; as well as other small ornaments. When it was introduced to the West in the mid-19th century, it was thought to be previously unknown outside Asia, but recent studies have suggested close similarities to certain decorative alloys used in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. read more

4995.00 GBP

A Fabulous Wakizashi by Master Sadahide Student of Masahide Dated 1830

A simply wonderful wide and sizeable blade with fine hamon and incredible tight grain hada. Copper patinated fushi kashira of the ‘tiger in the bamboo grove’. A very good signed copper tsuba with samurai. Original black lacquer saya with fine kozuka utility knife. As Sukehiro and Shinkai were highly praised by Kamada Natae in his book he wrote in this period swordsmiths begun to imitate their works making strong shape and Hamon in Toran-Ha. Swords in this period imitated the Osaka style. Then Masahide ( one of most famous sword smiths in Shinshinto time ) advocated in his book that "we should make swords by the method of the Koto era." With this final aim swordsmiths begun to create their own steels trying to reach the quality of the ancient one. Combining materials which have different quantity of carbon, a good Jihada will appear. Therefore, swordsmiths used a lot of materials like old nails and the like to adjust the quantity of carbon to be suitable for swordmaking.Even today this steel is called Oroshi-gane. As already said an easy way to produce Tamahagane was available in Shinto time and swordsmith could get good quality Tamahagane. Therefore, it seems that most of them didn't make their own Oroshi-gane. But some swordsmiths like Kotetsu or Hankei followed Masahide suggestions and reached a top-quality level combining ancient iron/steel with modern one. In effect Ko-Tetsu means "ancient steel". Exceptionally powerful 16inch blade read more

5450.00 GBP