A Beautiful Ancient Bronze and Enamel Book Clasp Around 1100 Years Old. From the Era of Anglo Saxon England & The Viking Incursions into Britain Through to The Early Crusades Period

Circa 10th-12th century AD. A stunning and most beautiful antiquity perfect for an antiquarian bibliophile as an example of the rarest of artefacts used to protect valuable volumes illuminated manuscripts and testaments.

A small and most intricate gem from the days of the Anglo Saxon’s and Vikings.

Originally from the Christian Eastern Roman Empire. A bronze tongue-shaped clasp with pelleted border and reserved peacock on an enamelled field. Anglo Saxon to early Norman period. Very fine condition. Two examples in the gallery show a 1000 year old book and a 1000 year old old testament that both had clasps such as this. The Bible is an ancient text. Like every other ancient text, the originals have not survived the ravages of time. What we have are ancient copies of the original which date to hundreds of years after their composition, for example from around 700 AD This is normal for ancient texts. For example, Julius Caesar chronicled his conquest of Gaul in his work On The Gallic War in the first century B.C. The earliest manuscript in existence dates to the 8th century AD, some 900 years later. The oldest biblical text is on the Hinnom Scrolls ? two silver amulets that date to the seventh century B.C. These rolled-up pieces of silver were discovered in 1979-80, during excavations led by Gabriel Barklay in a series of burial caves at Ketef Hinnom. When the silver scrolls were unrolled and translated, they revealed the priestly Benediction from Num 6:24-26 reading, ?May Yahweh bless you and keep you; May Yahweh cause his face to Shine upon you and grant you Peace.?6 The Ketef Hinnom scrolls contain the oldest portion of Scripture ever found outside of the Bible and significantly predate even the earliest Dead Sea Scrolls. They also contain the oldest extra-biblical reference to YHWH. Given their early date, they provide evidence that the books of Moses were not written in the exilic or postexilic period as some critics have suggested.

Richard Lassels, an expatriate Roman Catholic priest, first used the phrase “Grand Tour” in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy, published posthumously in Paris in 1670. In its introduction, Lassels listed four areas in which travel furnished "an accomplished, consummate traveler" with opportunities to experience first hand the intellectual, the social, the ethical, and the political life of the Continent.

The English gentry of the 17th century believed that what a person knew came from the physical stimuli to which he or she has been exposed. Thus, being on-site and seeing famous works of art and history was an all important part of the Grand Tour. So most Grand Tourists spent the majority of their time visiting museums and historic sites.

Once young men began embarking on these journeys, additional guidebooks and tour guides began to appear to meet the needs of the 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors traveling a standard European itinerary. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England, enabling them to access money and invitations along the way.

With nearly unlimited funds, aristocratic connections and months or years to roam, these wealthy young tourists commissioned paintings, perfected their language skills and mingled with the upper crust of the Continent.

The wealthy believed the primary value of the Grand Tour lay in the exposure both to classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite society of the European continent. In addition, it provided the only opportunity to view specific works of art, and possibly the only chance to hear certain music. A Grand Tour could last from several months to several years. The youthful Grand Tourists usually traveled in the company of a Cicerone, a knowledgeable guide or tutor.

The ‘Grand Tour’ era of classical acquisitions from history existed up to around the 1850’s, and extended around the whole of Europe, Egypt, the Ottoman Empire, and the Holy Land. The book clasp is 10.4 grams, 38mm (1 1/2" inches long)

The dirt from the rear surface of the object was removed manually using a scalpel under magnification. Care was taken not to dislodge the powdery, corroding surface. With all hand conservation if the surface is in particularly sensitive condition the dirt was left in situ read more

1295.00 GBP

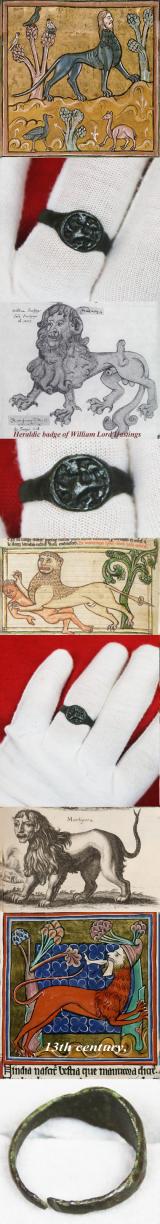

Wonderful 12th-13th Century Crusader & Pilgrim Knight's Heraldic Seal Ring Of a Fantastical Beast The Manticore, A Human Headed Tiger or Lion. Used In Medeavil Heraldry On Shields, Banner, Accoutrements & Indicated To Which Noble Family A Knight Belonged

A superb naturally patinated bronze, realistically engraved with an intaglio of the Manticore a Man-Tiger or Man-Lion. For example, in the 1400's it was the Heraldic Badge of William Lord Hastings. Often used as a supporter for a noble coat of arms. The ring is also very unusual in that it is designed to be sectioned on the inside ring so as to be self adjusting for finger size.

The royal supporters of England are the heraldic supporter creatures appearing on each side of the royal arms of England. The royal supporters of the monarchs of England displayed a variety, or even a menagerie, of real and imaginary heraldic beasts, either side of their royal arms of sovereignty, including lion, leopard, panther and tiger, manticore, antelope and hart, greyhound, boar and bull, falcon, cock, eagle and swan, red and gold dragons, as well as the current unicorn.

In ancient Greek culture, the manticore represented the unknown lands of Asia, the area it was said to inhabit. In later times, the manticore was recognized by many Europeans as a symbol of the devil or of the ruthless rule of tyrants. This may have originated in the practice of using manticores as royal decorations, and heraldic devices.

The Manticore In Art, Literature, And Everyday Life

During the Middle Ages, the manticore appeared in a number of bestiaries, books containing pictures or descriptions of mythical beasts.

The manticore was also featured in medieval heraldry—designs on armour, shields, and banners that indicated the group or family to which a knight belonged.

The medieval Maniticore is featured in numerous medieval manuscripts known as Bestiary, a book written in the Middle Ages containing descriptions of real and imaginary animals, intended to teach morals, religion and to entertain.

The bestiary — the medieval book of beasts — was among the most popular illuminated texts in northern Europe during the Middle Ages (about 500–1500). Medieval Christians understood every element of the world as a manifestation of God, and bestiaries largely focused on each animal's religious meaning. Much of what is in the bestiary came from the ancient Greeks and their philosophers. The earliest bestiary in the form in which it was later popularized was an anonymous 2nd-century Greek volume called the Physiologus, which itself summarized ancient knowledge and wisdom about animals in the writings of classical authors such as Aristotle's Historia Animalium and various works by Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, Solinus, Aelian and other naturalists.

Following the Physiologus, Saint Isidore of Seville (Book XII of the Etymologiae) and Saint Ambrose expanded the religious message with reference to passages from the Bible and the Septuagint. They and other authors freely expanded or modified pre-existing models, constantly refining the moral content without interest or access to much more detail regarding the factual content. Nevertheless, the often fanciful accounts of these beasts were widely read and generally believed to be true. A few observations found in bestiaries, such as the migration of birds, were discounted by the natural philosophers of later centuries, only to be rediscovered in the modern scientific era.

Medieval bestiaries are remarkably similar in sequence of the animals of which they treat. Bestiaries were particularly popular in England and France around the 12th century and were mainly compilations of earlier texts. The Aberdeen Bestiary is one of the best known of over 50 manuscript bestiaries surviving today.These bestiaries held much content in terms of religious significance. In almost every animal there is some way to connect it to a lesson from the church or a familiar religious story. With animals holding significance since ancient times, it is fair to say that bestiaries and their contents gave fuel to the context behind the animals, whether real or myth, and their meanings.

UK size R1/2 read more

595.00 GBP

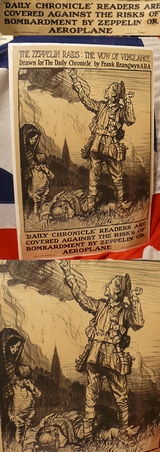

A Most Fine and Rare Original Frank Brangwyn WW1 Propaganda Poster. A Superb Piece Of Original Historical WW1 Artistry,Ideal For Interior Decor

This is a superb original work of art that would look simply amazing framed and placed in the right setting.

After the June 1915 raids, when air raids intensified, the Daily Chronicle offered its readers £150 for damage to homes and their contents by hostile aircraft, £100 for fatal injuries, £30 for damage inflicted by the enemy but not by air power and £10 to cover medical fees for non-fatal injuries.

The Zeppelin Raids: the vow of vengeance. Drawn for "The Daily Chronicle" by Frank Brangwyn A.R.A. 'Daily Chronicle' readers are covered against the risks of bombardment by zeppelin or aeroplane.British infantryman, full-length standing figure, looking up and shaking his fist at a departing Zeppelin. At his feet lies the body of an old woman who is mourned by a small boy and woman, left. In the background a skyline of bomb damaged and smoke shrouded buildings text: "THE ZEPPELIN RAIDS: THE VOW OF VENGEANCE Drawn for 'The Daily Chronicle' by Frank Brangwyn ARA" (in 2 lines upper edge) & "'DAILY CHRONICLE' READERS ARE COVERED AGAINST THE RISKS OF BOMBARDMENT BY ZEPPELIN OR AEROPLANE" printed by The Avenue Press, Ltd., Bouverie St., London, E.C. Original lithograph poster.

There are other original surviving examples of this original poster in both the Imperial War Museumin London and the Library of Congress in America. Posters of this kind are rare simply due to the fact they were considered as disposable propaganda artworks and were thus disposed of when no longer needed after the wars end. Brangwyn trained at the Royal College of Art, and was an apprentice with the designer William Morris. A highly regarded and prolific draughtsman, he was an established Royal Academician by the beginning of the First World War.

Frank Pick, General Manager of London Underground and a notable supporter of high quality design, commissioned Brangwyn to produce morale raising posters for London commuters. Brangwyn also worked extensively for war charities, producing many posters in support of Belgian relief, as he had been born in Bruges. Later in the war he contributed to the Ministry of Information's print series 'Efforts and Ideals' and designed posters for the National War Savings Committee.

His emotive realism was often criticised by government officials for demoralising the public. His depiction of close combat in the War Savings poster 'Put Strength in the Final Blow' was published only after some debate. The poster caused a public outcry in Germany, but ironically Brangwyn's reputation was considerably higher on the Continent. He was featured in an illustrated article in the prestigious German poster journal, Das Plakat in 1919.

Moved by the suffering and destruction of the war, Brangwyn later became a pacifist. His career continued to flourish after the war, most prominently as a painter of murals for public buildings. He is celebrated in the Brangwyn Museum in Bruges and the Musee de la Ville at Orange, France also has large holdings of his work. During World War I, the impact of the poster as a means of communication was greater than at any other time during history. The ability of posters to inspire, inform, and persuade combined with vibrant design trends in many of the participating countries to produce interesting visual works. At the start of the twentieth century he was the one British artist whose work was revered by the European cognoscenti, and the Japanese recognised in his artistic endeavours a love of simplicity, geometric compositions, and clarity of colour. He worked for Bing and Tiffany and produced murals for four North American public buildings. A supremely charitable man with a reputation for being irascible; a pacifist whose brutal WWI poster Put Strength in the Final Blow (1918) reputedly led the Kaiser to put a price on his head.

The man whom G K Chesterton described as

‘the most masculine of modern men of genius’ could also produce exquisitely delicate and serene works like St Patrick in the Forest (Christ’s Hospital murals); and his oils are as voluptuous in colour and form as his furniture is minimalist. Original WW1 and WW2 Posters are becoming hugely popular yet some are still very affordable, prices for nice examples are reaching well into the thousands over the past few years now. If a 1920's Russian movie poster of the Battleship Potemkin will fetch over £100,000 GBP, the potential for the values of fine propaganda posters by the great artists of their day could be immense 20 x 30.25 inches read more

625.00 GBP

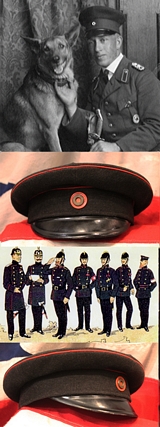

Used In WW1 & WW2. An Imperial German Issued Peaked Cap for Fire Protection Officer of Lubeck. Used From WW1 & Through to Early WW2 After The Organisation Was Taken Over By Himmler’s SS

A rare service cap, that is historically very interesting indeed, yet remarkably affordable.

Blue wool cloth with two red piping borders and single red and brass disc roundel. In super condition, worn areas to the lining and sweatband, as to be expected, but the peak and dark blue cloth are superb.

Made in WW1 Imperial period, worn right through the later Weimar period and into the early Third Reich era. When used in the Third Reich era, by the Fire Protection Police, it was an organization that was an auxiliary to the Ordnungspolizei, and during the war was absorbed into the SS. Feuerschutzpolizei. By 1938, all of Germany's local fire brigades were part of the ORPO. Orpo Hauptamt had control of all civilian fire brigades. ORPO's chief was SS-Oberstgruppenfuhrer Kurt Daluege who was responsible to Himmler alone until 1943 when Daluege had a massive heart attack.

From 1943, Daluege was replaced by Obergruppenfuhrer Alfred Wunnenberg until May 1945.

ORPO was structurally reorganised by 1941. It had been divided into the numerous offices covering every aspect of German law enforcement in accordance with Himmler's desire for public control of all things.

A very attractive and interesting piece in super order and totally complete. read more

285.00 GBP

A Very Fine & Rare Pair of Cased WW1 Great War Imperial German Epaulettes. For An Officer Of Adolf Hitler’s War Service Bavarian Reserve Regiment. It Is Distinctly Possible He Served With The Later Fuhrer

For the Imperial German 40th Infantry officer. Used by the German regimental officers that fought in the trenches with Adolf Hitler's infantry, and apparently the 40th relieved to command Hitler's company within the List Regiment, the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16 (1st Company of the List Regiment).

Beautifully preserved In their original storage case in mint condition overall.

Mid blue cloth background with gilt crescent and Infantry number 40. Red back cloth.

During the war, Hitler served in France and Belgium in the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16 (1st Company of the List Regiment). He was an infantryman in the 1st Company during the First Battle of Ypres (October 1914), which Germans remember as the Kindermord bei Ypern (Ypres Massacre of the Innocents) because approximately 40,000 men (between a third and a half) of nine newly-enlisted infantry divisions became casualties in 20 days. Hitler's regiment entered the battle with 3,600 men and at its end mustered 611. By December Hitler's own company of 250 was reduced to 42. Biographer John Keegan claims that this experience drove Hitler to become aloof and withdrawn for the remaining years of war. After the battle, Hitler was promoted from Schutze (Private) to Gefreiter (Lance Corporal). He was assigned to be a regimental message-runner

The List Regiment fought in many battles, including the First Battle of Ypres (1914), the Battle of the Somme (1916), the Battle of Arras (1917), and the Battle of Passchendaele (1917). During the Battle of Fromelles on 19?20 July 1916 the Australians, mounting their first attack in France, assaulted the Bavarian positions. The Bavarians repulsed the attackers, suffering the second-highest losses they had on any day on the Western Front, about 7,000 men read more

385.00 GBP

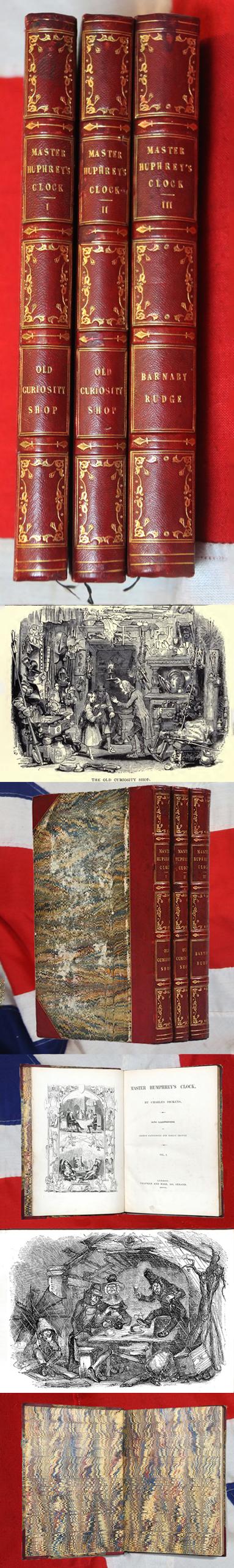

An Absolutely Perfect Discerning Collectors Piece, by Charles Dickens. A Fabulous 3 Volume Charles Dickens Ist Edition, The Old Curiosity Shop & Barnaby Rudge, In, Master Humphrey's Clock. London: Chapman and Hall, 1840-41,

Alongside A Christmas Carol, the Old Curiosity Shop ranks as a true iconic tale of Victorian England, and ideal for the Christmas season.

Could one imagine anything better than settling down to read, or better still, to be read to, over a few cosy candle lit nights, a succession of Dicken’s short stories. These are the very first, original volumes, that were read at the very same time, in the very same same way, but some two centuries ago in Victorian England, and likely, dozens of times subsequently since by their various, most fortunate owners.

First edition of this collection of short stories. Large octavo, 3 volumes bound in red half morocco over marbled boards with gilt tooling to the spine in five compartments within raised gilt bands, morocco spine labels lettered in gilt, top edge gilt, marbled endpapers, engraved frontispiece to each volume, illustrated by George Cattermole and Hablot Browne. In very good condition.

Master Humphrey's Clock was a weekly serial that contained both short stories and two novels (The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge). Some of the short stories act as frame stories to the novels so the ordering of publication is important. Although Dickens' original artistic intent was to keep the short stories and the novels together, he himself cancelled Master Humphrey's Clock before 1848, and described in a preface to The Old Curiosity Shop that he wished the story to not be tied down to the miscellany it began within. Most later anthologies published the short stories and the novels separately. However, the short stories and the novels were published in 1840 in three bound volumes under the title Master Humphrey's Clock, which retains the full and correct ordering of texts as they originally appeared.

First edition in book form of what Gordon Ray describes as "the pinnacle of Dickensian Gothic". He goes on to note that Phiz (H. K. Browne) "is in excellent form" and that George Cattermole's "wonderful clutter of antiquarian or architectural detail is well suited to Dickens's chosen subjects".

Master Humphrey was a publishing experiment on Dickens's part, unique in his canon, of issuing two novels together: The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge.

3 volumes, large octavo (256 x 173 mm). Contemporary red half morocco, marbled sides ruled in gilt, spines lettered, ruled, and tooled in gilt, marbled endpapers, top edges gilt, green silk bookmarkers.

Printed frontispieces and 194 woodcut illustrations, of which 154 are by Browne, 19 by Cattermole, and 1 by Daniel Maclise.

Covers rubbed, slight rubbing and wear to extremities, vol. I front joint split at foot but remains firm, light foxing to margins, small marks to a few pages, generally bright. A superb set.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Eckel, p. 67 ff; Ray, The Illustrator and the Book in England from 1790 to 1914, 60; Smith I, 6. read more

1795.00 GBP

A Most Scarce & Collectable 1935 Issue WW2 Luftwaffe Combat Helmet M35 NS62 Single Decal But Only Partialy Visible. Stamped Batch Number D128. with Original Liner And Partial Chin Strap

Overall in jolly nice condition.

The liner is named for the Luftwaffe officer or airman.

Arguably the helmet was the most recognizable part of the individual German soldiers appearance. With a design that derived from the type used in world war one, the German helmet offered more protection then ones used by it’s enemies. The quality luftwaffe gray painted steel helmet with decals and rolled steel rim and leather liner was a labour intensive product and simplified as the war progressed.

The earliest model helmet used in world war two was this model 35 or M35 Stahlhelm. During the war the helmet was simplified in 2 stages. In 1940 the airvents changed from separate rivets affixed {as has this one} to the helmet shell to stamped in the main body of the shell. In 1942 a new model was introduced where the rim of the shell was left sharp and not rolled over as previous models. These models are known in the collector community as M40 and M42. The low sides that protect the neck and ears, the tell tale design that the Germans introduced in 1935 can still be seen in modern day army helmets.

The WW2 German helmet maker "NS" stands for Vereinigte Deutsche Nickelwerke AG (United German Nickelworks) located in Schwerte, a major manufacturer producing steel helmets (Stahlhelm) 62 is the helmets size. read more

1100.00 GBP

A Spectacular Condition, Original, British 1885 Pattern Cavalry Trooper's Combat Sabre. The Sword Used to Incredible Effect At the Battle of Omdurman. Stamped WD Broad Arrow, And Issue Date 1885. {War Department} Complete With Buff Hide Sword Knot

A simply stunning 1885 Pattern Cavalry Sword. This sword has been incredibly well cared for and it is amazing condition. It would, without a shadow of a doubt, be impossible to improve upon with a better example. as good if not better than the very best examples in the National Army Museum or The Tower of London collection.

After a false start in 1882, the 1885 pattern was developed following committee input on improving the sword. The first opposite ringed scabbard came out of this process along with a slightly shorter blade. This sword saw extensive use in the campaigns in Egypt and the Sudan during the 1880s and 1890s. The shortening of the blade did allow some opponents along the Nile to lie on the ground, putting themselves out of the reach of the trooper's sword! This problem was rectified in the 1899 pattern. Still this sword represented an important step in the evolution of British Cavalry swords and was used by the 21st Lancers at the Battle of Omdurman in 1898; amongst the daring lancers was a young Winston Churchill.

The Battle of Omdurman was fought during the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan between a British–Egyptian expeditionary force commanded by British Commander-in-Chief (sirdar) major general Horatio Herbert Kitchener and a Sudanese army of the Mahdist State, led by Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, the successor to the self-proclaimed Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. The battle took place on 2 September 1898, at Kerreri, 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) north of Omdurman.

Following the establishment of the Mahdist State in Sudan, and the subsequent threat to the regional status quo and to British-occupied Egypt, the British government decided to send an expeditionary force with the task of overthrowing the Khalifa. The commander of the force, Sir Herbert Kitchener, was also seeking revenge for the death of General Gordon, who had been killed when a Mahdist army captured Khartoum thirteen years earlier.3 On the morning of 2 September, some 35,000–50,000 Sudanese tribesmen under Abdullah attacked the British lines in a disastrous series of charges; later that morning the 21st Lancers charged and defeated another force that appeared on the British right flank. Among those present was 23-year-old soldier and reporter Winston Churchill as well as a young Captain Douglas Haig.

The victory of the British–Egyptian force was a demonstration of the superiority of a highly disciplined army equipped with modern rifles, machine guns, and artillery over a force twice its size armed with older weapons, and marked the success of British efforts to reconquer Sudan. Following the Battle of Umm Diwaykarat a year later, the remaining Mahdist forces were defeated and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan was established.

Pictures in the gallery of photographs of the regimental armourers sharpening their 1885 cavalry swords before combat. read more

785.00 GBP

A Scarce US Civil War Service 1817 Model US Army Rifle, Dated 1826, Percussion Conversion For American The Civil War

Made in Middleton Connecticut by either Simeon North or Robert Johnson. The breech is marked in three lines with US / AH / (circle) P. The P proof mark is in a depressed rosette. The inspector initials AH are those of Asabel Hubbard who was a Springfield Armory armourer and contract arms inspector.

The M1817 nicknamed the 'common rifle' in order to distinguish it from the Hall rifle was a flintlock muzzle-loaded weapon issued due to the US Dept. of Ordnance's order of 1814, produced by Henry Deringer and used from 1820s to 1840s at the American frontier, and after conversion to percussion, in the American Civil War in the 1860's.

This type of rifle-musket was used in the Civil War with service in the 2nd Mississippi Infantry, CS. A seldom seen, good looking longarm to fit any military collection, with shortened fore-stock wood, smooth bored.

Under contract with the government, Henry Deringer converted some 13,000 such flintlocks to percussion, muzzleloader rifles with the ‘drum’ or ‘French’ style system.

Unlike the half-octagon barreled Model 1814 Rifle that preceded it, it had a barrel that was round for most of its length. The barrel was rifled for .54 calibre bullets. For rifling it had seven grooves. Like the Model 1814, it had a distinctive large iron oval patchbox in the buttstock. read more

1345.00 GBP

A Wonderful Museum Grade Masterpiece, A Rare 18th Century French Small-Sword of Purest Gold Applied to Lustrous Crafted Silver & Hand Chiselled Steel. As Fine As Anything Comparable in the Royal Collection, or Les Invalides Army Museum in Paris.

A stunning museum grade sword, a pure masterpiece of the sword makers art! Magnificently decorated with purest gold, applied to the finest hand chiselled steel, worthy of a finest collection of 18th to 19th century fine art, decor and furnishings. A singular example of the skill of the artists in the French king’s and the later Emperor Napoleon’s court. Almost all of the executed King’s artisans were recruited by Napoleon for his service at the Emperor’s court..

Likely made at Versailles by a Royal swordsmith of King Louis XVIth, such as the master swordsmiths of the king, Lecourt, Liger or Guilman. A very finest grade sword of the form as was made for the king to present to favoured nobles and friends. He presented a similar sword to John Paul Jones see painting in the gallery now in the US Naval Academy Museum. Three near identical swords to this now reside in the Metropolitan. This is a simply superb small-sword, with stunningly engraved chiselled steel hilt, overlaid with pure gold over a fish-roe background, decorated with hand chiselled patterns of scrolling arabesques throughout the hilt, knucklebow, shell guards and pommel in the rococo style. The multi wire spiral bound grip is finest silver, betwixt blued silver bands, with Turks head finials. The blade is in the typical trefoil form, ideal for the gentleman's art of duelling, and very finely engraved. The degree of craftsmanship of this spectacular sword is simply astounding, worthy of significant admiration, it reveals an incredible attention to detail and the skill of it's execution is second to none.

A four figure piece that could easily be five figures if it was only known to whom it was presented. A secret lost into the mists of time!

Other similar swords are in also in the British Royal Collection and in Les Invalides in Paris. Trefoil bladed swords had a special popularity with the officers of the French and Indian War period. Even George Washington had a very fine one just as this example. For example of the workmanship in creating this sword, for such as the King and Marie Antoinette, the keys for the Louis XVI Secretary Desk (Circa 1783) made for Marie-Antoinette by Jean Henri Riesener, one of the worlds finest cabinetmakers, and whose works of furniture are the most valuable in the world. The steel and gold metalwork key for Marie Antoinette's desk, is attributed to Pierre Gouthire (1732-1813), the most famous Parisian bronzeworker of the late eighteenth century who became gilder to the king in 1767. This sword bears identical workmanship and style to that magnificent key.

This is the quality of sword one might have expected find inscribed upon the blade 'Ex Dono Regis' given by the King.

Very fine condition overall, with natural aged patination throughout.

Of course a masterpiece of this level could, and will, never be created again, however, if one could, only the gold and steel master gunsmiths such as the finest craftsman employed by such as Purdey of London, might even attempt to. And the cost?, without doubt, around £150,000 {plus}.

The painting in the gallery, is titled John Paul Jones and Louis XVI, by the American artist Jean Leon Gerome Ferris depicts John Paul Jones and Benjamin Franklin at the court of Louis XVIth and being presented a similar sword now in US Naval Academy Museum.

Overall length 35.5 inches read more

5995.00 GBP