Japanese

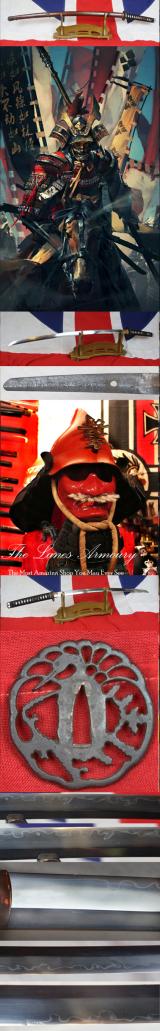

A Superb, Original, Antique Japanese Shinshinto Period, 19th Century, Samurai's, Secret, Hidden Fan-Dagger, A Kanmuri-Otoshi Form Kakushi Ken

A fantastic original antique samurai conversation piece, a samurai tanto {dagger} disguised as a folded fan, that the blade is concealed within. A wide and very attractive kanmuri-otoshi form kakushi ken, with clip back return false edge, overall bright polish and just the faintest traces of miniscule old age pitting. Edo period secret bladed tanto,19th century, with carved wood and bi-colour urushi lacquered fittings, in ishime black and golden yellow, beautifully simulated to look like a traditional Japanese folded fan.

A photo in the gallery from Edo Japan of a seated high ranking samurai holding his tachi and war fan. Another samurai standing also with fan and daisho through his obi. Samurai sometimes disguised their blades as inoffensive items, such as cleverly made walking sticks or other common objects such as fans. Their ancestors, the classical warriors, overlooked nothing which could be used as a weapon. Also, deprived of their swords by law in the Meji era, late 19th century samurai had to rely even more on their own ingenuity and resourcefulness for protection against thieves, hoodlums, bandits and intrigue. The blade nakago sealed in place, so there was no telltale visible mekugi blade affixing peg.

A Japanese war fan is a fan designed for use in warfare. Several types of war fans were used by the samurai class of feudal Japan and each had a different look and purpose. One particularly famous legend involving war fans concerns a direct confrontation between Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin at the fourth battle of Kawanakajima. Kenshin burst into Shingen's command tent on horseback, having broken through his entire army, and attacked; his sword was deflected by Shingen's war fan. It is not clear whether Shingen parried with a tessen, a dansen uchiwa, or some other form of fan. Nevertheless, it was quite rare for commanders to fight directly, and especially for a general to defend himself so effectively when taken so off-guard.

Minamoto no Yoshitsune is said to have defeated the great warrior monk Saito Musashibo Benkei with a tessen.

Araki Murashige is said to have used a tessen to save his life when the great warlord Oda Nobunaga sought to assassinate him. Araki was invited before Nobunaga, and was stripped of his swords at the entrance to the mansion, as was customary. When he performed the customary bowing at the threshold, Nobunaga intended to have the room's sliding doors slammed shut onto Araki's neck, killing him. However, Araki supposedly placed his tessen in the grooves in the floor, blocking the doors from closing. Types of Japanese war fans;

Gunsen were folding fans used by the average warriors to cool themselves off. They were made of wood, bronze, brass or a similar metal for the inner spokes, and often used thin iron or other metals for the outer spokes or cover, making them lightweight but strong. Warriors would hang their fans from a variety of places, most typically from the belt or the breastplate, though the latter often impeded the use of a sword or a bow.

Tessen were folding fans with outer spokes made of heavy plates of iron which were designed to look like normal, harmless folding fans or solid clubs shaped to look like a closed fan. Samurai could take these to places where swords or other overt weapons were not allowed, and some swordsmanship schools included training in the use of the tessen as a weapon. The tessen was also used for fending off knives and darts, as a throwing weapon, and as an aid in swimming.

Gunbai (Gumbai), Gunpai (Gumpai) or dansen uchiwa were large solid open fans that could be solid iron, metal with wooden core, or solid wood, which were carried by high-ranking officers. They were supposedly used to ward off arrows, as a sunshade, and to signal to troops.

12 inches long overall. approx 7.5 inch blade. The black ishime lacquer is near pristine, the golden yellow urushi lacquer has some natural, dark, handling age staining. read more

1320.00 GBP

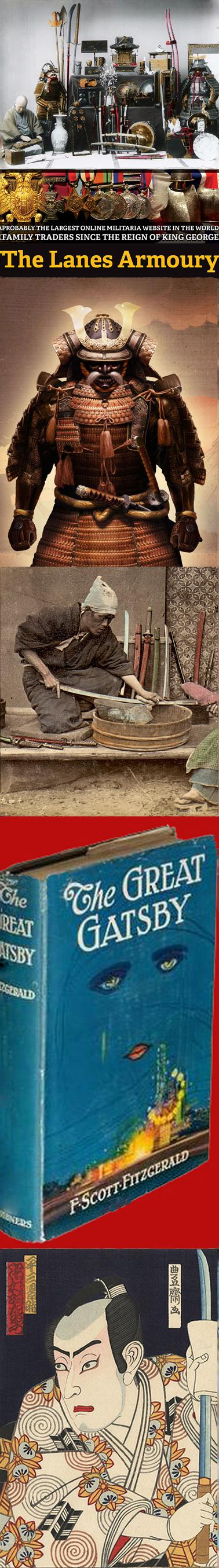

The Lanes Armoury, Often Referred As Britain’s Favourite Antique Gallery. Family Traders, For Many Generations In The Lanes Over 100 Years & 200 Years As General Merchants In Brighton. We Are Also Europe’s Leading Original Samurai Sword Specialists

another fantastic collection of original samurai swords have just arrive, ready for cleaning and conservation.

We are the leading and pre-eminent original samurai sword specialists in the whole of Europe, in fact, we know of no other specialists outside of Japan, and likely within it, that stock anywhere near the quantity of our original selection. Constantly striving to achieve the very best for all our clients from around the world, our solution demanded a holistic approach and a strategic vision of what can be achieved. A solution that has effectively taken over 100 years in the making, and thus in order to be improved upon, it is evolving, constantly. However, never forgetting our old fashioned values of a personal, one to one service, dedicated for the benefit of our customers.

We even had the enormous privilege, to own and sell, although, sadly, only very briefly, thanks to the kind assistance of the most highly esteemed Japanese sword expert in England, Victor Harris, an incredibly rare and unique sword, an original, Edo period, traditionally hand made representation facsimile of the most famous Japanese sword in world history, the Japanese National Treasure, Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi (草薙の剣). It is a legendary Japanese sword and one of three Imperial Regalia of Japan. It was originally called Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi (天叢雲剣, "Heavenly Sword of Gathering Clouds"), but its name was later changed to the more popular Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi ("Grass-Cutting Sword"). In folklore, the sword represents the virtue of valour. Victor stated it was the only example he had ever seen, possibly an official Imperial commission, to create for the emperor and scholars a faithful, identical facsimile of the most treasured sword ever made in Japan’s history. The National Treasure sword is used only during the coronation of the Emperor, yet even the emperor is not permitted to gaze upon it {apparently} only to place his hand upon it, beneath its ceremonial silk cloth.

Our one time late advisor, Victor Harris, was Curator, Assistant Keeper and then Keeper (1998-2003) of the Department of Japanese Antiquities, at the British Museum. He studied from 1968-71 under Sato Kenzan, of the Tokyo National Museum and Society for the Preservation of Japanese Swords. We fondly remember many brainstorming sessions on our ever expanding collection of ancient antique and vintage Japanese swords with Victor, and our late esteemed colleague, Chris Fox, formerly a member of the Nihonto of Great Britain Association, here in our store.

After well over 54 years of personal experience as a professional dealer by Mark, since 1971, and David’s experiance over 44 years, we are now universally recognised as Europe’s leading samurai sword specialists, with many hundreds of swords to view and buy online 24/7, or, within our store, on a personal visit, 6 days a week. In fact we know of no better and varied original samurai sword selection for sale under one roof outside of Japan, or probably, even within it. Hundreds of original pieces up to 800 years old. Whether we are selling to our clients representing museums around the globe, the world’s leading collectors, or simply a first time buyer, we offer our advice and guidance in order to assist the next custodian of a fine historical Japanese sword, to make the very best, and entirely holistic choice combination, of a sword, its history, and its {koshirae} fittings.

But that of course is just one small part of the story and history of The Lanes Armoury, and the Hawkins brothers, as the world famous arms armour, militaria & book merchants

Both of the partners of the company have spent literally all of their lives surrounded by objects of history, trained, almost since birth in the arts, antiques and militaria. Supervised and mentored, first by their grandfathers, then their father, who left the RAF sometime after the war, to become one of the leading antique exporters and dealers in the entire world. Selling, around the globe, through our network of numerous shops, warehouses, and antique export companies, in today’s equivalent, hundreds of millions of pounds of our antiques and works of art. Our family have traded as general merchants for over 200 years in Brighton, including supplying the Prince Regent {King George IVth} shellfish to his palace in Brighton, The Royal Pavilion.

Both Mark and David were incredibly fortunate to be mentored by some of the world’s leading experts within their fields of antiques and militaria. For example, just to mention two of Mark’s diverse mentors, one was Edward ‘Ted’ Dale, who was one of Britain's most highly respected and leading experts on antiques in his day. He was chief auctioneer and managing director in the 1960’s and 70’s of Bonhams Auctioneers of London, now one of the worlds highest ranked auctioneers, and at the other end of the spectrum, there was Bill ‘Yorkie’ Cole, the company’s ‘keeper of horse’, who revelled in the title of the company’s ‘head stable boy’, right up until his 90’s, in fact, he refused to retire, he simply ‘faded away’. He controlled our stables and dozens of horse drawn vehicles up to the 1970’s. He was a true Brighton character, whose experiences in the antique trade went way back to WW1, and, amongst other skills, he taught young Mark, as a teenager in the 1960’s, to drive a horse drawn pantechnicon with ‘Dolly’, Britain’s last surviving English dray horse that was trained for night driving in the ‘blackout’ during the blitz. See a photo of the company pantechnicon and 'Dolly' in the gallery

Mark has been a director and partner in the family businesses since 1971, specialising in elements of the family business that varied from the acquisition and export of vintage cars, mostly Rolls Royces, Bentleys, Aston Martins and Lagondas, to America, to the complete restoration and furnishing of a historical Sussex Georgian country Manor House for his late mother from the ground up, but long before that he was handling and buying swords and flintlocks since he was just seven years old, obviously in a very limited way though, naturally.

David jnr, Mark’s younger brother, also started collecting militaria when he was seven, in fact he became the youngest firearms dealer licence holder in the country, and it was he that convinced Mark that concentrating on militaria and rare books was the future for our world within the antique trade, and as you will by now guess, history, antiques, books and militaria are simply in their blood.

Thus, around 40 years ago, they decided to sell their export business and concentrate where their true hearts lie, in the world of military history and its artefacts, from antiquity to the 20th century. From fine and rare books and first editions, to antiquities and the greatest historical and beautiful samurai swords to be found. One photo in the gallery was one of the rarest books we have ever had, some years ago, a Great Gatsby Ist edition they can now command up to $360,000

One photo in the gallery is of Mark, some few years ago with his then new lockdown companion at the farm, ‘Cody’, named after Buffalo Bill naturally. Cody is now somewhat bigger! .Another photo is of two of our ten company trucks photographed just after their delivery from the signwriters. As you can see we always enjoyed a very old fashioned British tradition of having our vehicles fully liveried, hand sign written and artistically painted by our local and very talented artisans. Vehicles that ranged from our many horse drawn vehicles, to our 1930’s Bedford generator lorry that doubled up during WW2 as a mobile searchlight for the local anti-aircraft artillery installations, and then to our more modern fleet from the 1950’s to the 1980’s. The green liveried Leyland truck in the photograph was hand painted with a massive representation of the scene of the chariot race from Chuck Heston’s movie spectacular Ben Hur, and on the other side a huge copy of Lady Butler’s Charge of the Heavy Brigade. Each painting took over three months to complete. When we called Chuck in America to show him the completed livery, painted in his honour, he was delighted and very impressed and promised to visit us again to see it personally in all its glory, sadly his filming schedules for his 1970’s blockbuster disaster movies such as ‘Earthquake’ prevented it. Chuck was recommended to us years before by one of his co-stars in Solyent Green, one of Hollywood’s true greats, {alongside Chuck} Edward G. Robinson, who used to buy, undervalued {then}, impressionist paintings from David snr in the 1960’s. read more

Price

on

Request

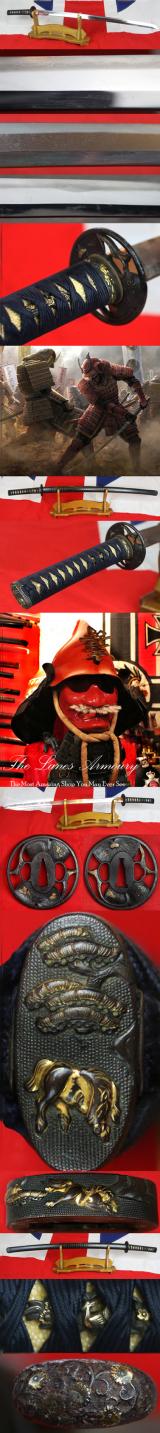

An Absolute Beauty of a Fine, Koto Period Katana, Signed Bishu Osafune Kiyomitsu & Dated 1573 The Tsuba is Kinai School, a Sukashi Round Tsuba, of An Aoi,

A very good Koto period sword, with a beautiful polished blade. Two stage black lacquer saya with two tone counter striping at the top section and ishime stone matt lacquer at the bottom, it has an iron Higo style kojiri bottom chape inlaid with gold. The fuchigashira are shakudo copper with a nanako ground decorated with takebori carved ponies over decorated in pure gold, with bocage of a Japanese white pine tree above the pony on the kashira. The tsuba is a Kinai school sukashi round tsuba, in the form of an aoi, or hollyhock plant heightened with gold inlays, including Arabesque scrolls, and leaves. the tsuba came from likely a branch of the Miochin (Group IV), this family was founded by Ishikawa Kinai, who moved from Kyoto to Echizen province and died in 1680. The succeeding masters, however, bore the surname of Takahashi. All sign only Kinai Japanese text, with differences in the characters used and in the manner of writing them.

Futaba aoi is a Japanese term for the Asarum caulescens plant, which has two leaves and is often mistakenly called a "hollyhock" due to its use in the Aoi Matsuri festival. The distinctive heart-shaped leaves of futaba aoi are used to decorate participants and items in the Aoi Matsuri, which is a major festival in Kyoto. The plant is sacred to the Shimogamo and Kamigamo shrines and also served as the crest for the powerful Tokugawa Shogunate family.

The Kinai made guards only, of hard and well forged iron usually coated with the black magnetic oxide. They confined themselves to pierced relief showing extraordinary cleanness both of design and execution. Any considerable heightening of gold is found as a rule only in later work. Dragons in the round appear first in guards by the third master, fishes, birds, etc., in those of the fifth; while designs of autumn flowers and the like come still later. There are examples of Kinai tsuba in the Ashmolean and the British Museum. Made around to decades before but certainly used in the time of the greatest battle in samurai history "The Battle of Sekigahara" Sekigahara no Tatakai was a decisive battle on October 21, 1600 that preceded the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. Initially, Tokugawa's eastern army had 75,000 men, while Ishida's western army numbered 120,000. Tokugawa had also sneaked in a supply of arquebuses. Knowing that Tokugawa was heading towards Osaka, Ishida decided to abandon his positions and marched to Sekigahara. Even though the Western forces had tremendous tactical advantages, Tokugawa had already been in contact with many daimyo in the Western Army for months, promising them land and leniency after the battle should they switch sides.

Tokugawa's forces started the battle when Fukushima Masanori, the leader of the advance guard, charged north from Tokugawa's left flank along the Fuji River against the Western Army's right centre. The ground was still muddy from the previous day's rain, so the conflict there devolved into something more primal. Tokugawa then ordered attacks from his right and his centre against the Western Army's left in order to support Fukushima's attack.

This left the Western Army's centre unscathed, so Ishida ordered this unit under the command of Shimazu Yoshihiro to reinforce his right flank. Shimazu refused as daimyos of the day only listened to respected commanders, which Ishida was not.

Recent scholarship by Professor Yoshiji Yamasaki of Toho University has indicated that the Mori faction had reached a secret agreement with the Tokugawa two weeks earlier, pledging neutrality at the decisive battle in exchange for a guarantee of territorial preservation, and was a strategic decision on Mori Terumoto's part that later backfired.

Fukushima's attack was slowly gaining ground, but this came at the cost of exposing their flank to attack from across the Fuji River by Otani Yoshitsugu, who took advantage of this opportunity. Just past Otani's forces were those of Kobayakawa Hideaki on Mount Matsuo.

Kobayakawa was one of the daimyos that had been courted by Tokugawa. Even though he had agreed to defect to Tokugawa's side, in the actual battle he was hesitant and remained neutral. As the battle grew more intense, Tokugawa finally ordered arquebuses to fire at Kobayakawa's position on Mount Matsuo to force Kobayakawa to make his choice. At that point Kobayakawa joined the battle as a member of the Eastern Army. His forces charged Otani's position, which did not end well for Kobayakawa. Otani's forces had dry gunpowder, so they opened fire on the turncoats, making the charge of 16,000 men mostly ineffective. However, he was already engaging forces under the command of Todo Takatora, Kyogoku Takatsugu, and Oda Yuraku when Kobayakawa charged. At this point, the buffer Otani established was outnumbered. Seeing this, Western Army generals Wakisaka Yasuharu, Ogawa Suketada, Akaza Naoyasu, and Kutsuki Mototsuna switched sides. The blade is showing a very small, combat, sword to sword, thrust from a blade tip, or, possibly a deflected arrow impact, this tiny wound so to speak should never be polished away, this is known as a most honourable battle scar, and certainly no detriment to the blade, and that likely saved the owner of the swords life in a hand to hand combat situation. See close up photo 9 in the gallery, tiny impact of around 1mm with slight bruising below over a maximum total length 5mm, max impact depth around 1mm read more

8750.00 GBP

A Fine Signed Shinto O-Tanto Signed Yamoto Daijo Kanehiro.

Signed Shinto Tanto, by a master smith bearing the honorific title Assistant Lord of Yamoto.

A Samurai's personal dagger signed Yamoto Daijo Kanehiro. A Smith who had a very high ranking title A very nice signed Tanto, in full polish, with an early, Koto, Kamakuribori Style Iron Tsuba. The tsuba is probably Muromachi period around 1450, carved in low relief to one side. 6.5cm. Plain early iron Koshira. The blade in nice polish, itami grain and a medium wide sugaha hamon signed with his high ranking official title Yamoto Daijo Kanehiro [Kane Hiro, Assistant Lord of Yamoto Province] circa 1660. He lived in Saga province. Superb original Edo period ribbed lacquer saya.the saya has a usual side pocket to fit a kozuka utility knife. These knives were always a separate non matching and disconnected part of the dagger. Black silk binding over silver feather menuki. The samurai were bound by a code of honour, discipline and morality known as Bushido or ?The Way of the Warrior.? If a samurai violated this code of honour (or was captured in battle), a gruesome ritual suicide was the chosen method of punishment and atonement. The ritual suicide of a samurai or Seppuku can be either a voluntary act or a punishment, undertakan usually with his tanto or wakazashi. The ritual suicide of a samurai was generally seen as an extremely honourable way to die, after death in combat. read more

3995.00 GBP

A Most Scarce Antique Samurai Commander's Saihai, A Samurai Army Signalling Baton

Edo period. From a pair of different forms of saihai acquired by us.

For a commander to signal troop movements to his samurai army in battle. A Saihai, a most lightweight item of samurai warfare, and certainly a most innocuous looking instrument, despite being an important part of the control of samurai troop movements in combat, usually consisted of a lacquered wooden haft with metal ends. The butt had a hole for a cord for the saihai to be hung from the armour of the samurai commander when not being used. The head of the saihai had a hole with a cord attached to a tassel of strips of lacquered paper, leather, cloth or yak hair, rarest of all used metal strips. This example uses yak hair.

We show the lord Uesugi Kenshin holding his in an antique woodblock print in the gallery.

The saihai first came into use during the 1570s and the 1590s between the Genki and Tensho year periods. Large troop movements and improved and varied tactics required commanders in the rear to be able to signal their troops during a battle Uesugi Kenshin (February 18, 1530 - April 19, 1578) was a daimyo who was born as Nagao Kagetora, and after the adoption into the Uesugi clan, ruled Echigo Province in the Sengoku period of Japan. He was one of the most powerful daimyos of the Sengoku period. While chiefly remembered for his prowess on the battlefield, Kenshin is also regarded as an extremely skillful administrator who fostered the growth of local industries and trade; his rule saw a marked rise in the standard of living of Echigo.

Kenshin is famed for his honourable conduct, his military expertise, a long-standing rivalry with Takeda Shingen, his numerous campaigns to restore order in the Kanto region as the Kanto Kanrei, and his belief in the Buddhist god of war Bishamonten. In fact, many of his followers and others believed him to be the Avatar of Bishamonten, and called Kenshin "God of War". read more

650.00 GBP

A Singularly Fabulous Ancient Koto Period 15th Century Katana Circa 1480. Very Likely Formerly a Nodachi Great Sword. Officially Shortened by Bakufu Edict To Katana Length in 1617. With Stunning Heianjo School Tsuba

A very fine and beautiful and most rare 600 year old Koto katana that looks absolutely spectacular, with an o-suriage blade, with full length hi groove, and with a notare hamon that undulates with extraordinary depth into the blade.

The tang has two intersperced mekugiana, {mounting peg holes} the current one being several inches from the other, which would indicate it was an incredibly long sword, a nodachi or odachi.

To qualify as an odachi, the sword in question must have had an original blade length over 3 shaku (35.79 inches or 90.91 cm).

However, as with most terms in Japanese sword arts, there is no exact definition of the size of an odachi.

The odachi's importance died off after the Siege of Osaka of 1615 (the final battle between Tokugawa Ieyasu and Toyotomi Hideyori). The Bakufu shogunal government set a law which prohibited holding swords above a set length (in Genna 3 (1617), Kan'ei 3 (1626) and Shoho 2 (1645)).

After the law was put into practice, odachi were cut down to the shorter legal size. This is one of the reasons why odachi are so rare.

Since then many odachi were shortened to use as katana, we feel this was when have been when this blade was shortened, likely in 1617.

Odachi or Nodachi were very difficult to produce because their length makes heat treatment in a traditional way more complicated: The longer a blade is, the more difficult (or expensive) it is to heat the whole blade to a homogenous temperature, both for annealing and to reach the hardening temperature. The quenching process then needs a bigger quenching medium because uneven quenching might lead to warping the blade.

The blade has no combat damage of any kind, just natural surface minuscule age pin prick marks, and it has been untouched since it came to England in the 1870's.

All original Edo mounts and saya, with Higo mounts inlaid with gold leaves and tendrils, and original Edo period turquoise blue tsuka-ito (柄糸) over gold and shakudo menuki (目貫):of flowers, on traditional giant rayskin samegawa.

The saya is finely ribbed with silk cord ribbing under black lacquer, with carved buffalo horn kurigata (栗形) and kaeshizuno (返し角) and It has a fine and large four lobed mokko gata tsuba (鍔 or 鐔) form, with punch marks, sekigane inserted in the nakago ana, a look of a great strength, and a lightly hammered ground to effect a stone like surface, on the both sides, from the natural folding of the plate. It is pierced in delicate manner on top and bottom with stylised warabite, bracken shoots, and on either side of the central opening with large irregular ryohitsu shaped apertures of two hisago. The iron plate is finely inlaid on both sides and on the rounded rim with a thin roped band made in brass, and decorated all around the edge in brass hirazogan in a design of bellflower blossoms, clementis leaves and tendrils, flushing to the surface, and known as Chinese grass or karasuka. The formal design in negative silhouette is straightforward, the lowering of the level of the surface between the rim and the seppadai contributes to a sense of stability, the metal has a deep purplish patina, and the entire guard has a rustic appearance. This very pleasing masterpiece exhibits a nice feel due to the simplicity of the design.

This ko sukashi work is the ultimate in simplification. this severe, unemotional work is a deep humanity that speaks to us today. This strict style marks the dividing line between youthful severity and older warm humanity. All of these traits make this an exceptoional work of Heianjo school, in a style influenced by workers of Yoshiro school of the Koike family in Kyoto and as a gift from one Daimyo to another. The size, quality of inlay, and condition all confirm the excellent craftsmanship characteristic of this school. This is probably a transition piece between the Onin and the Heianjo school. This style of tsuba often given the designation of Heianjo school, could also be from the last period of onin brass inlay style of the Muromachi period. Yoshiro tsuba are originated from the Heianjo Zogan school, active in the second half of the 16th century. Naomasa was the most famous member of the large Koike family school, he took the technique and style to the highest level. Early Edo period tsuba. 17th Century. Overall condition of the tsuba is excellent.

To place it in context as to just how old this sword is, in its British time-scale comparison, it was made, in Japan, in the era of the 'Wars of the Roses' between King Richard IIIrd and King Henry VIIth.

A long {28 inches in length} blade, measured tsuba to tip read more

9450.00 GBP

A Beautiful Shinto Katana By Kaga Kiyomitsu With NTHK Kanteisho Papers

With super original Edo period koshirae mounts and fittings. Higo fuchigashira with pure gold onlay with a war fan and kanji seal stamp. Shakudo menuki under the hilt wrap of samurai warriors fighting with swords and polearm. Iron plate o-sukashi tsuba, black lacquer saya with buffalo horn kurigata. Superb hamon and polish with just a few aged surface stains see photo 7

The Hamon is the pattern we see on the edge of the blade of any Nihonto (日本刀) and it is not merely aesthetic, but is due to the differential tempering with clay applied to weapons in the forging process. Japanese katanas are unique in the way of the forging process, where apart from the materials the system is tremendously laborious. In short, before temper, the steel has different clays applied that when submerged in water causing the characteristic blade curvature and the pattern of the hamon. This also causes the katanas to be flexible and can be very sharp, since the hardening of the steels at different temperatures causes a part of the sword to be softer and more flexible called Mune or loin and the other harder and brittle, thus having a High quality cutting edge capable of making precise and lethal cuts.

There are various types and variants, some simple and others very complex. Depending on how the clay is applied, it will form some patterns or others.

According to legend, Amakuni Yasutsuna developed the process of differential hardening of the blades around the 8th century. The emperor was returning from battle with his soldiers when Yasutsuna noticed that half of the swords were broken:

Amakuni and his son, Amakura, picked up the broken blades and examined them. They were determined to create a sword that will not break in combat and they were locked up in seclusion for 30 days. When they reappeared, they took the curved blade with them. The following spring there was another war. Again the soldiers returned, only this time all the swords were intact and the emperor smiled at Amakuni.

Although it is impossible to determine who invented the technique, surviving blades from Yasutsuna around AD 749–811 suggest that, at the very least, Yasutsuna helped establish the tradition of differentially hardening blades.

By the time Ieyasu Tokugawa unified Japan under his rule at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, only samurai were permitted to wear the sword. A samurai was recognised by his carrying the feared daisho, the big sword daito, little sword shoto of the samurai warrior. These were the battle katana, the big sword, and the wakizashi, the little sword. The name katana derives from two old Japanese written characters or symbols: kata, meaning side, and na, or edge. Thus a katana is a single-edged sword that has had few rivals in the annals of war, either in the East or the West. Because the sword was the main battle weapon of Japan's knightly man-at-arms (although spears and bows were also carried), an entire martial art grew up around learning how to use it. This was kenjutsu, the art of sword fighting, or kendo in its modern, non-warlike incarnation. The importance of studying kenjutsu and the other martial arts such as kyujutsu, the art of the bow, was so critical to the samurai, a very real matter of life or death, that Miyamoto Musashi, most renowned of all swordsmen, warned in his classic The Book of Five Rings: The science of martial arts for warriors requires construction of various weapons and understanding the properties of the weapons. A member of a warrior family who does not learn to use weapons and understand the specific advantages of each weapon would seem to be somewhat uncultivated. We rarely have swords with papers for our swords mostly came to England in the 1870's long before 'papers' were invented, and they have never returned to Japan for inspection and papers to be issued. However, on occasion we acquire swords from latter day collectors that have had swords papered in the past 30 years or so., and this is one of those. read more

7450.00 GBP

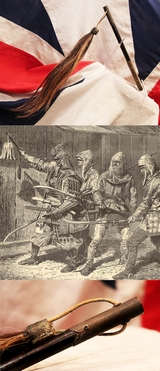

A Rare, Original, Japanese Antique Edo Period Samurai War Bow 'Daikyū ' With Urushi Lacquered Woven Rattan Quiver 'Yabira Yazutsu' With 3 'Ya' Arrows

A wonderful, original, antique Edo period {1603-1863} Samurai long war bow 'Yumi', made in either yohonhigo or gohonhigo form {4 piece or 5 piece bamboo laminate core, that is surrounded by wood and bamboo, then bound with rattan and lacquered}

Acquired by us by personally being permitted to select from the private collection one of the world's greatest, highly respected and renown archery, bow and arrow experts. Who had spent his life travelling the world to lecture on archery and to accumulate the finest arrows and bows he could find. .

Edo Era, 1600 to 1700's, with practice arrows, unfeathered, that fit into in a lacquer quiver {yabira yazutsu} with three arrows {ya}. we show a photo in the gallery from a samurai museum display that shows a practice arrow stand with the same form of flightless 'ya' inbedded in sand within the stand.

The arrows are made using yadake bamboo (Pseudosasa Japonica), a tough and narrow bamboo long considered the choice material for Japanese arrow shafts. The lidded quiver is a beautiful piece of craftsmanship in hardened urushi lacquer on woven rattan. Practice arrows were a fundamental part of samurai bowmanship.

These sets are very rarely to be seen and we consider ourselves very fortunate, indeed privileged, to offer another one.

It was from the use of the war bow or longbow in particular that Chinese historians called the Japanese 'the people of the longbow'. As early as the 4th century archery contests were being held in Japan. In the Heian period (between the 8th and 12th centuries) archery competitions on horseback were very popular and during this time training in archery was developed. Archers had to loose their arrows against static and mobile targets both on foot and on horseback. The static targets were the large kind or o-mato and was set at thirty-three bow lengths and measured about 180cm in diameter; the deer target or kusajishi consisted of a deer's silhouette and was covered in deer skin and marks indicated vital areas on the body; and finally there was the round target or marumono which was essentially a round board, stuffed and enveloped in strong animal skin. To make things more interesting for the archer these targets would be hung from poles and set in motion so that they would provide much harder targets to hit. Throughout feudal Japan indoor and outdoor archery ranges could be found in the houses of every major samurai clan. Bow and arrow and straw targets were common sights as were the beautiful cases which held the arrows and the likewise ornate stands which contained the bow. These items were prominent features in the houses of samurai. The typical longbow, or war bow (daikyu), was made from deciduous wood faced with bamboo and was reinforced with a binding of rattan to further strengthen the composite weapon together. To waterproof it the shaft was lacquered, and was bent in the shape of a double curve. The bowstring was made from a fibrous substance originating from plants (usually hemp or ramie) and was coated with wax to give a hard smooth surface and in some cases it was necessary for two people to string the bow. Bowstrings were often made by skilled specialists and came in varying qualities from hard strings to the soft and elastic bowstrings used for hunting; silk was also available but this was only used for ceremonial bows. Other types of bows existed. There was the short bow, one used for battle called the hankyu, one used for amusement called the yokyu, and one used for hunting called the suzume-yumi. There was also the maru-ki or roundwood bow, the shige-no-yumi or bow wound round with rattan, and the hoko-yumi or the Tartar-shaped bow. Every Samurai was expected to be an expert in the skill of archery, and it presented the various elements, essence and the representation of the Samurai's numerous skills, for hunting, combat, sport and amusement, and all inextricably linked together.

The mounted archer mainly controls his horse with his knees, as he needs both hands to draw and shoot his bow. As he approaches his target, he brings his bow up and draws the arrow past his ear before letting the arrow fly with a deep shout of In-Yo-In-Yo (darkness and light).

Yabusame (流鏑馬) is a type of mounted archery in traditional Japanese archery. An archer on a running horse shoots three special "turnip-headed" arrows successively at three wooden targets.

This style of archery has its origins at the beginning of the Kamakura period. Minamoto no Yoritomo became alarmed at the lack of archery skills his samurai possessed. He organized yabusame as a form of practice.

Nowadays, the best places to see yabusame performed are at the Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū in Kamakura and Shimogamo Shrine in Kyoto (during Aoi Matsuri in early May). It is also performed in Samukawa and on the beach at Zushi, as well as other locations.

On his final day in Japan in May 1922, Edward, Prince of Wales was entertained by Prince Shimazu Tadashige (1886–1968), son of the last feudal lord of the Satsuma domain. Lunch was served at Prince Shimazu’s villa, followed by an archery demonstration. Afterwards, the Prince of Wales was presented with a complete set for archery practice, including an archer’s glove, arm guard and reel for spare bowstrings read more

3550.00 GBP

A Fine Shinto Samurai Katana Signed By Mino Swordsmith, Nodagoro Fujiwara Kanesada Circa 1720 Around 300 Years Old, With a Horai-zu Style Tsuba

He also signed Kinmichi. see Hawley’s Japanese Swordsmiths, ID KAN533 who was active in the Mino province between 1716-1736. A beautiful sword with a fabulous hamon mounted handachi style. The photos showpresent It is an original Edo period mounted handachi semi tachi form katana with iron mounts of fine quality. The original Edo saya has a beautiful rich red lacquer with flecks of pure gold.

The Edo tsuba is o-sukashi, in iron, a Horai-zu style tsuba that has a motif of crane, the symbol of long life. The crane and/or turtle and/or rocks and/or pine trees and/or bamboo are often referred to as a 蓬莱図 (Hōrai-zu) crane pattern design. The sword was being worn more and more edge up when on foot, but edge down on horseback as it had always been. The handachi is a response to the need to be worn in either style. The samurai were roughly the equivalent of feudal knights. Employed by the shogun or daimyo, they were members of hereditary warrior class that followed a strict "code" that defined their clothes, armour and behaviour on the battlefield. But unlike most medieval knights, samurai warriors could read and they were well versed in Japanese art, literature and poetry. Samurai were expected to be both fierce warriors and lovers of art, a dichotomy summed up by the Japanese concepts of bu to stop the spear exanding into bushido (the way of life of the warrior) and bun (the artistic, intellectual and spiritual side of the samurai).

Originally conceived as away of dignifying raw military power, the two concepts were synthesized in feudal Japan and later became a key feature of Japanese culture and morality.The quintessential samurai was Miyamoto Musashi, a legendary early Edo-period swordsman who reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday and was also a painting master. Members of a hierarchal class or caste, samurai were the sons of samurai and they were taught from an early age to unquestionably obey their mother, father and daimyo. When they grew older they could be trained by Zen Buddhist masters in meditation and the Zen concepts of impermanence and harmony with nature. The were also taught about painting, calligraphy, nature poetry, mythological literature, flower arranging, and the tea ceremony. The blade shows a super hamon, and polish with a couple of very small edge pits near the habaki on just one side. read more

8750.00 GBP

A Stunning Edo Period Tettsu {iron Plate} Krishitan {Christian.} Tsuba, Of The Holy Cross, Heavenly Eight Pointed Stars in Gold, & The River Of Life in Silver. In Superb Condition & From A Very Fine Collection of Tsuba.

A stunning Krishitam sukashi piercing of the cross with a silver river and gold eight pointed star inlays. With a kozuka hitsu-ana, and kogai hitsu ana

The Bible starts with an account of a river watering the Garden of Eden. It flowed from the garden separating out into four headwaters. The rivers are named, flowing into different areas of the world,

Eight pointed stars symbolise the number of regeneration and of Baptism. The Stars and The River as Christian Symbols, are images or symbolic representation with sacred significance. The meanings, origins and ancient traditions surrounding Christian symbols date back to early times when the majority of ordinary people were not able to read or write and printing was unknown. Many were 'borrowed' or drawn from early pre-Christian traditions.

The Hidden Christians quieted their public expressions and practices of faith in the hope of survival from the great purge. They also suffered unspeakably if captured and failed to renounce their Christian beliefs.

In Silence, Endo depicts the trauma of Rodrigues’ journey into Japan through his early encounter with an abandoned and destroyed Christian village. Rodrigues expresses his distress over the suffering of Japanese Christians and he reports the “deadly silence.”

‘I will not say it was a scene of empty desolation. Rather was it as though a battle had recently devastated the whole district. Strewn all over the roads were broken plates and cups, while the doors were broken down so that all the houses lay open . . . The only thing that kept repeating itself quietly in my mind was: Why this? Why? I walked the village from corner to corner in the deadly silence.

...Somewhere or other there must be Christians secretly living their life of faith as these people had been doing . . . I would look for them and find out what had happened here; and after that I would determine what ought to be done.”

- Silence, Shusaku Endo

Two images in the gallery are drawings of bronze fumi-e in use during the 1660s in Japan, during the time of the persecution. Each of these drawings mirrors actual brass fumi-e portraying Stations of the Cross, which are held in the collections of the Tokyo National Museum

The current FX series 'Shogun' by Robert Clavell is based on the true story of William Adams and the Shogun Tokugawa Ieyesu, and apart from being one of the very best film series yet made, it shows superbly and relatively accurately the machinations of the Catholic Jesuits to manipulate the Japanese Regents and their Christian convert samurai Lords.

Oda Nobunaga (1534–82) had taken his first step toward uniting Japan as the first missionaries landed, and as his power increased he encouraged the growing Kirishitan movement as a means of subverting the great political strength of Buddhism. Oppressed peasants welcomed the gospel of salvation, but merchants and trade-conscious daimyos saw Christianity as an important link with valuable European trade. Oda’s successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–98), was much cooler toward the alien religion. The Japanese were becoming aware of competition between the Jesuits and the Franciscans and between Spanish and Portuguese trading interests. Toyotomi questioned the reliability of subjects with some allegiance to the foreign power at the Vatican. In 1587 he ordered all foreign missionaries to leave Japan but did not enforce the edict harshly until a decade later, when nine missionaries and 17 native Kirishitan were martyred.

After Toyotomi’s death and the brief regency of his adopted child, the pressures relaxed. However, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who founded the great Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867), gradually came to see the foreign missionaries as a threat to political stability. By 1614, through his son and successor, Tokugawa Hidetada, he banned Kirishitan and ordered the missionaries expelled. Severe persecution continued for a generation under his son and grandson. Kirishitan were required to renounce their faith on pain of exile or torture. Every family was required to belong to a Buddhist temple, and periodic reports on them were expected from the temple priests.

By 1650 all known Kirishitan had been exiled or executed. Undetected survivors were driven underground into a secret movement that came to be known as Kakure Kirishitan (“Hidden Christians”), existing mainly in western Kyushu island around Nagasaki and Shimabara. To avoid detection they were obliged to practice deceptions such as using images of the Virgin Mary disguised as the popular and merciful Bōsatsu (bodhisattva) Kannon, whose gender is ambiguous and whom carvers often render as female.

The populace at large remained unaware that the Kakure Kirishitan managed to survive for two centuries, and when the prohibition against Roman Catholics began to ease again in the mid-19th century, arriving European priests were told there were no Japanese Christians left. A Roman Catholic church set up in Nagasaki in 1865 was dedicated to the 26 martyrs of 1597, and within the year 20,000 Kakure Kirishitan dropped their disguise and openly professed their Christian faith. They faced some repression during the waning years of the Tokugawa shogunate, but early in the reforms of the emperor Meiji (reigned 1867–1912) the Kirishitan won the right to declare their faith and worship publicly.

Some wear to the gold and silver inlays on the reverse side. read more

1495.00 GBP